Why won’t my achilles pain go away?

Whether you’re an athlete, occasional marathoner, or a casual exerciser, chronic Achilles pain can be a frustrating and painful condition that interferes with your daily life. In this blog, we’ll explore the common causes of chronic Achilles pain, effective treatments using exercise and not passive modalities, alternative ways to deal with the issue that you might have not heard of before, and preventative measures for managing this condition.

After reading this blog, if you still need help with your training, injury rehab, or performance, reach out to us at Vital Strength Physiology HERE.

Anatomy of the Achilles Tendon

The achilles tendon is the largest and strongest tendon in the human body. If you’re like most people, you’ve probably never given much thought to this vital part of your anatomy, but as anyone who’s ever suffered from Achilles pain can tell you, it’s a force to be reckoned with.

Tendinopathies seem to explain the majority of achilles pain in most individuals (Järvinen et al, 2001), while heel pain, another common problem or complaint in individuals with ankle or achilles pain, is most commonly due to plantar fasciitis (Rosenbaum et al, 2014).

For the purpose of this article, we will focus on achilles pain, or pain over and around the achilles tendon, located here (highlighted in blue):

“The most common clinical diagnosis of Achilles overuse injuries is tendinopathy, which is characterized by a combination of pain and swelling in the Achilles tendon accompanied by impaired ability to perform strenuous activities.” (Järvinen et al, 2001).

Tendinopathy essentially is a broad umbrella term for painful conditions occurring in and around tendons in response to overuse. Recent research suggests little or no inflammation is present in these conditions.

So if no inflammation is present (therefore anti-inflammatories won’t work), and if your pain started due to overuse but you’ve rested your injury and experienced no improvement, what are you supposed to do next?

You might have even consulted professionals like physiotherapists, doctors, or podiatrists, and they may have even tried many things to help. The most common treatments for these conditions are passive treatments like:

- Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation (RICE protocol)

- Stretching, Massage, release of tight muscles around the area

- Injections into the tendon

- Insoles, heel pads, new shoes, heel lifts, etc

The problem with all of these solutions, despite them being the most commonly prescribed treatments, is that they are PASSIVE. They don’t require any active loading of the tendon, any activation from the brain to create the change. These solutions are TOO static for the most part.

BUT, BUT!

I hear you – there ARE some things that could have set you up for this injury that were somewhat out of your control. These common risk factors for developing achilles tendinopathies include:

- Chronic disease like Diabetes and Obesity (your BMI is over 30kg/m2)

- Increased tendon thickness

- Rigid insoles or shoes

- Genetics; if you have the gene for abnormal collagen production

- Weakness in muscles in the hip, knee and ankle

- Poor proprioception (Martin et al, 2018)

There can even be some biomechanical reasons for achilles pain, that while you are in control of changing, most people have no idea that they could contribute to achilles pain:

- Heel striking

- Poor form while walking running causing too much or too little pronation

- Too much pronation (which can also be caused by too much knee valgus/collapse) or flat feet

- Too little pronation (stiff or immobile feet or structures up the chain)

- Decreased strength of the foot ankle or knee causing excessive stress on one part of the chain in walking or running

So, let’s dive a little deeper.

Are some people more likely to get achilles pain?

The majority of those suffering from Achilles tendinopathy are active individuals, often involved in recreational or competitive sports. Estimates of the annual incidence of Achilles tendinopathy in runners range between 7% and 9%, however, cases have been reported in sedentary people as well. Although runners appear to be the most commonly affected by achilles disorders, they have been reported in a wide variety of sports – especially during the training seasons as competitive seasons approach.

While there is an increased prevalence of Achilles injury as age increases, the mean age of those affected by Achilles disorders is between 30 and 50 years. While sex does not appear to play a role in the risk of developing achilles injuries, it has been reported that males seem to be affected to a greater extent than females (Martin et al, 2018).

If this is beginning to sound like you… the runner or athlete, aged 30-50, who is actively training and wants to perform…. What can you do differently to your achilles to help resolve the ongoing pain?

Loading the Achilles Tendon

The Achilles takes a LOT of load, even when we’re “only” walking.

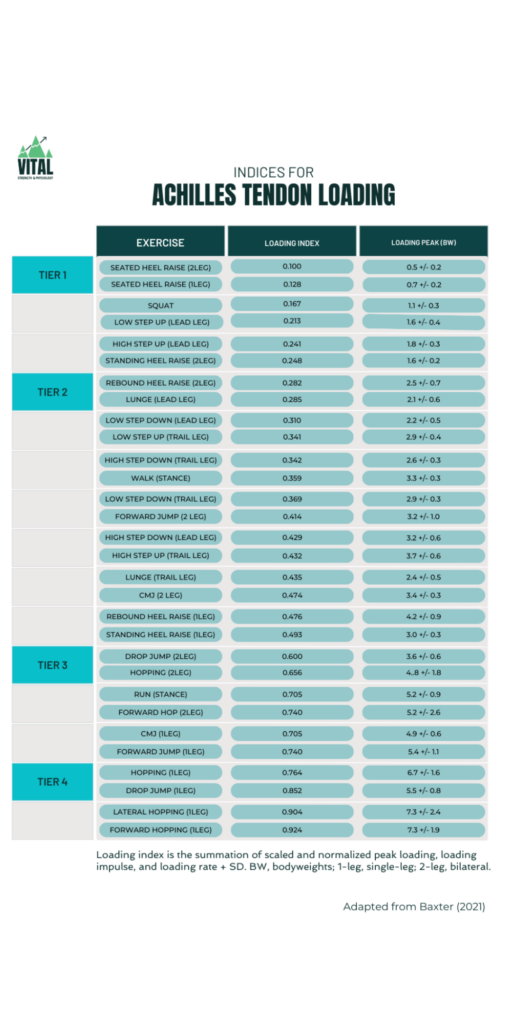

In the table below adapted by Baxter et al, you can a large list of exercises, categorized into 4 tiers of higher and higher loads on the achilles.

Essentially, an exercise like a squat loads the achilles about 1x body weight, whereas a CMJ (counter-movement jump – also known as a 2 legged jump where you quickly drop your body mass before jumping up in the air and landing) loads the achilles 3.4x your body weight! Progress the jump to a single leg jump (see CMJ – 1 leg), and you’re loading that achilles 4.9x your body weight! For a 150lb individual that’s 735lbs of load on the achilles!

With the table above in mind – your achilles might not currently be able to handle walking (which is about 1/4 down the table in terms of increasing load) – but it might be able to handle some calf raises without a flare up. Over time, it might be able to handle some single leg calf raises, and as you progress to harder exercises on the table above, the tendon might gradually be able to tolerate walking again, because it is only slighly more load than step downs or lunges in your exercise progression. We mentioned above that REST is not the answer for tendons, but the answer IS LOAD. Why?

Structurally, the Achilles tendon is made up of tough, fibrous tissue that’s surrounded by a thin layer of synovial fluid. This fluid helps to lubricate the tendon and reduce friction as it moves against other tissues in the body. Tendon is visco-elastic meaning it has properties of viscous materials like water, and elastic materials like rubber bouncy balls.

Tendons act more viscously in slow movements and more stiffly in fast movements. This is similar to slinking into a pool via the stairs – when you enter the water slowly, the water contours around you and doesn’t give much resistance to the entry. When you jump in and belly-flop into the pool, the fast movement creates more resistance on the water and can HURT, as the water doesn’t have time to move around you. Similarly, the water inside the tendon doesn’t have time to exit the tendon when you jump or run, which creates stiffness required to load the tendon more than the muscle.

Knowing that you’ll load the muscle more than the tendon in slow movements, and that you’ll load the tendon more than the muscle in fast movements, creating the stiffness you’re after, is helpful in explaining the rehabilitation process and getting out of chronic pain. Often we don’t realize it, but we flare up the tendon by returning to the fast movements too soon – something the tendon hasn’t progressed to.

Though slow movements load the tendon a little less than a fast movement, you have to start with slow movements, or even exercises that DON’T involve movement (as we will speak about later on), before you can progress to the dynamic ones. If you’re dealing with chronic achilles issues yourself, you’ll want to stick around till the end as we explain this below!

Causes of chronic achilles pain

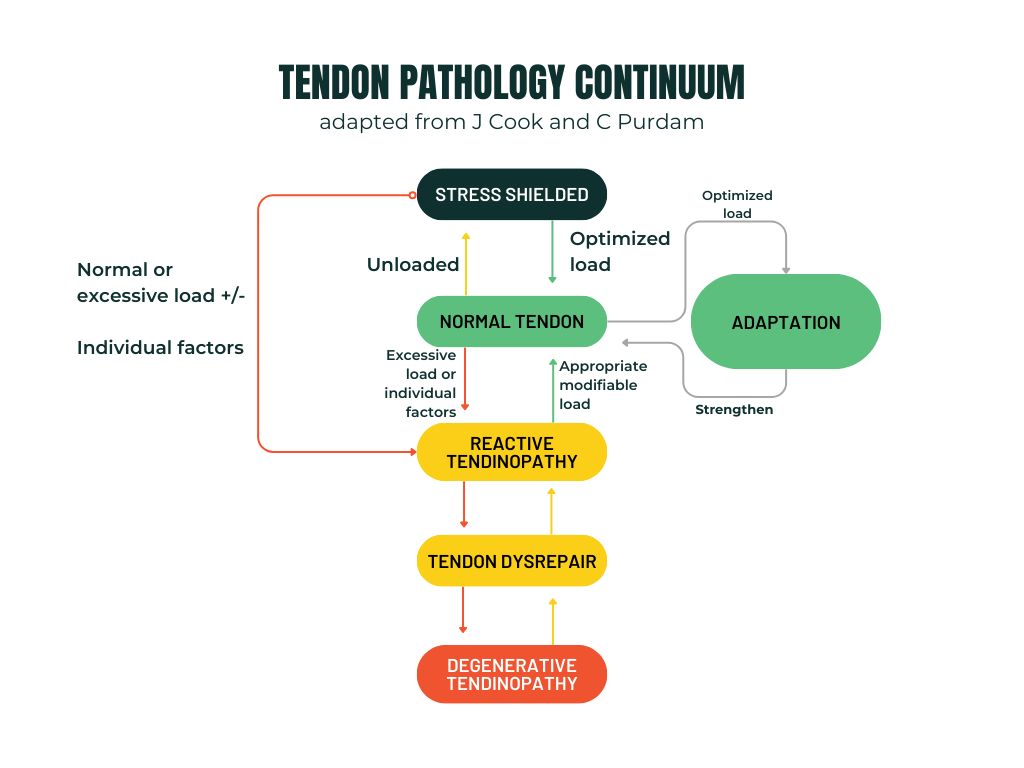

Chronic Achilles tendinopathy is a complex condition influenced by a variety of factors. This is Jill Cooks (the tendon research queen) area of expertise, so we have adapted her tendon continuum below for quick reference. We suggest reading more of her work if you’re interested in diving even deeper into this.

At Vital – we use a full individualized assessment to determine other areas that may need work or that could be contributing to the additional load on the achilles. The two main reasons we get injured are because of too much load too fast (an increase in volume or intensity that the area was not ready to handle), and mechanical factors like HOW you are doing the loading.

For example, if you tend to always spend a lot more time on your right leg when you run, or if you collapse your foot inwards creating a “C-shaped” achilles, these could load the tendon more on that side or in undesirable ways.

Although this blog is not about how to identify the mechanical factors and movement compensations, we want you to be aware that they do exist and could contribute. Now onto the stages of rehab you can try!

Common ways to rehab the Achilles Tendon

Common ways to rehab an Achilles problem involve PASSIVE solution. Passive solutions often don’t tackle the source of the problem but will be the number one method people try as they are “fast and easy”… though costly. These could include;

- Using a heel lift/heel cup/heel wedge

- Wearing a brace or night brace

- Rolling on a foam roller or lacrosse ball

- Physiotherapy/massage etc

Typically, when people are in pain, they only think about therapists and doctors as solutions. Therapists and doctors can absolutely be helpful in the rehab of injuries, but strength and rehab specialists also play a key role.

Active solutions involve loading the injury, and has been shown to be the only way to improve the tendon matrix. Often, people don’t try this for their achilles problem as they are “time consuming” and “energetically expensive” though they typically solve the problem long term.

“Exercise is the best intervention for tendinopathy, and is the only stimulus with the capacity to positively affect tendon matrix” – Gandersen et al (2015).

Active solutions include:

- Loading the achilles with calf raises and other exercises

- Progressively increasing volume (more sets or more exercise sessions throughout the week)

- Hiring a strength coach to progress your exercises

- Trying a program like Foot Foundations which helps strengthen not just the damaged tendon, but helps strengthen all of the structures in the surrounding area to take more load for the achilles

- Fixing Biomechanics so that we offload the ankle more

Loading the tendon is the only way to stimulate the body’s natural repair processes, so next we will take you through a basic guide on what you might consider doing for the loading/active portion of your rehab if your chronic achilles pain is not going away.

TRY FOOT FOUNDATIONS

Enjoying these perspectives on the achilles? Get 20% off our 12-week Foot Foundations program with code ACHILLES.

Achilles Tendon Rehabilitation: A Structured Approach using Jill Cook’s 3 stages

Phase 1: Isometric Loading – Building a Foundation

The journey to Achilles tendon recovery begins with isometric loading, a technique gaining prominence for its effectiveness in managing tendinopathy. Isometric loading means the muscle is contracting without changing length. These contractions work the degenerative or reactive tendon by allowing the stronger part of the tendon that is stress shielding the unhealthy tendon to relax, so that the unhealthy parts start to feel load that is crucial for their adaptation, that they have become shielded from. For more on stress-shielding – we made a post about that HERE.

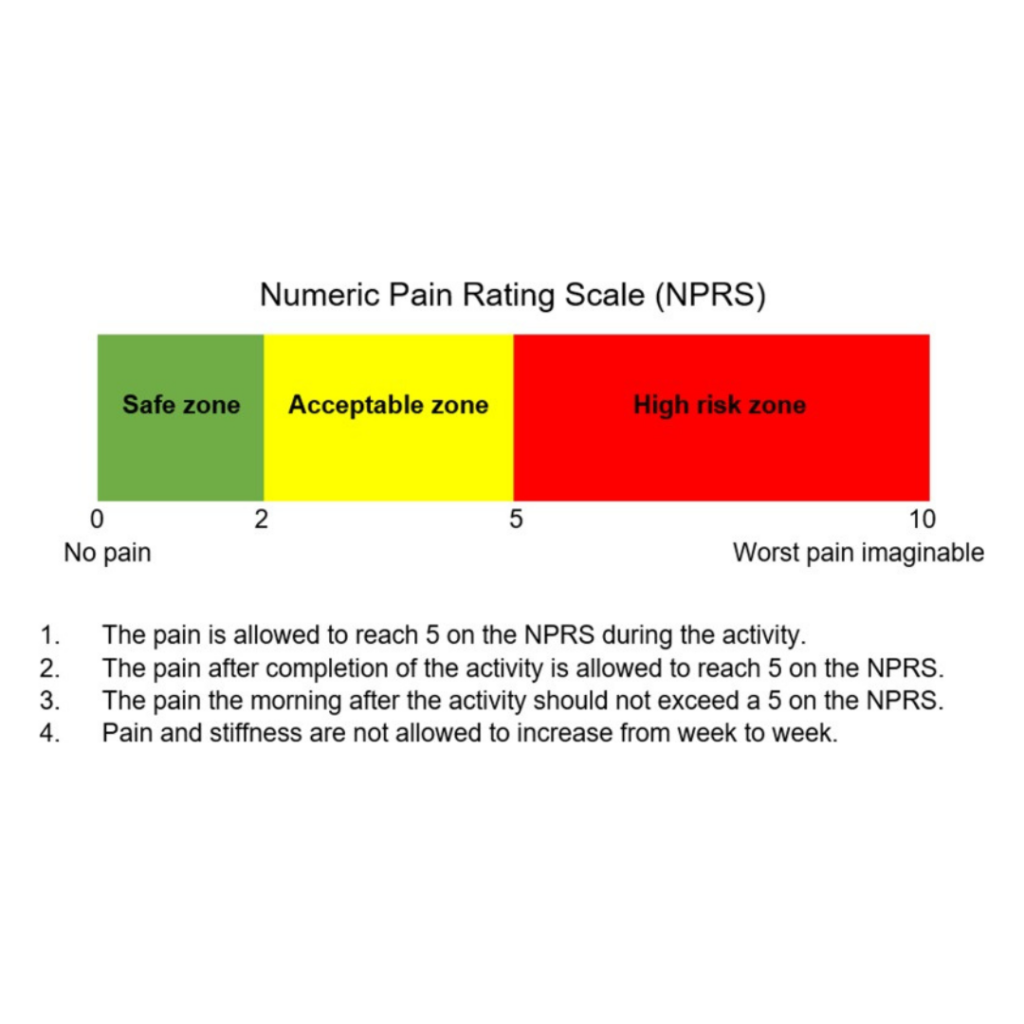

This phase focuses on reducing pain and preserving muscle strength through mostly static exercises. The key is to find the right balance between challenge and comfort, aiming for holds in the mid-range or fully elevated position. Using this scale by Finni et al (2023), perform the exercises below in this phase for 2-4 weeks or until pain subsides and you’re ready to try more loading.

- Single Leg Heel Raise Isometric Hold: A foundational exercise to stabilize and strengthen the tendon. Hold these for 30 seconds (IMPORTANT) with 2 minutes of rest (IMPORTANT) for 3-5 sets depending on pain and tolerance. You can also start with 2-leg isometric holds instead of single leg if this increases symptoms.

- Toe walking: A way to accumulate more isometric volume while adding some dynamic movement and working on keeping both heels (especially the affected side) high.

- Intrinsic foot strength drills: While you work on specific exercises for the calves, you can also start to incorporate some other intrinsic foot strengthening to bring up the loading capacity of the whole area

- In the meantime, if walking or running increases your symptoms in the achilles after the fact or the next day, lower your running or walking volume below the amount that caused the symptoms. Tendons are tricky as they might not hurt during the exercises but tendons often reveal if they were overloaded after the fact. Choose cross training methods like pool running or the elliptical or bike trainer to maintain fitness.

Phase 2: Isotonic Loading – Gaining Strength

Transitioning to isotonic loading (the muscle lengthens and shortens through a range of motion) marks a critical step in rehabilitation, initiated when pain becomes manageable and morning stiffness decreases. This phase aims to build tendon and muscle strength through dynamic exercises. Emphasis is placed on the calf muscles, crucial for Achilles tendon functionality. The exercises involve progressive loading, enhancing the tendon’s capacity to handle stress without overstraining.

(It should be noted that the isometrics from Phase 1 can be continued through all the phases and are especially helpful for decreasing pain acutely).

- Isotonic Seated Calf Raises: Focuses on building strength in a seated position, gradually increasing the load.

- Isotonic Standing Calf Raises: Performed in the muscle’s mid-range to avoid tendon compression, using heavy slow resistance training.

- Single Leg Bent Knee (Soleus) Calf Raises: this deeper calf muscle is one of the most crucial ones for running, and due to it’s shared Achilles tendon with the other calf muscle the Gastrocnemius, it’s important to train them both! Do this with more bend in the knee than a typical calf raise.

- In this phase, you can start re-introducing a run/walk program or low-level exercises from the Baxter table linked above in this blog. Choose exercises that don’t aggravate the area while progressing you lower and lower to higher load exercises on the table.

Phase 3: Energy Storage and Release Loading – Enhancing Performance

The final phase introduces plyometric exercises to restore the tendon’s ability to store and release energy efficiently. This stage is suitable for individuals with minimal morning stiffness and who have progressed well through previous exercises up to, but not including, the CMJ (countermovement jump) load on the Baxter table above. The goal is to prepare the tendon for high-impact activities through exercises that involve jumping and hopping, simulating real-world sports movements. Remember that tendons get their stiffness and the most adaptation from fast movements, so stopping your rehab short of this stage will NOT be enough to take you all the way.

Feel free to keep your isometrics and exercises from Phase 2 through to Phase 3, in lower volumes. By Phase 3 you can drop the volume (sets) of exercises by ⅓.

- Deep, Medium, and Light Double-leg Leaps (jumping from two legs to two legs; can use a skipping rope): Builds bilateral strength and endurance.

- Deep, Medium and Light Single leg Bounds (jumping from one leg and landing on the other): these will be of higher intensity and load than the leaps, but will be less load than the single leg hops to follow.

- Deep, Medium, and Light Single-leg Hops (jumping from one leg and landing on the same leg): Increases strength and stability on each leg independently.

This structured approach, from isometric holds through isotonic exercises to dynamic plyometrics, outlines a comprehensive path to Achilles tendon recovery, emphasizing gradual progression tailored to individual tolerance and recovery stages.

Prevention of achilles pain

Preventing Achilles tendinopathy involves understanding its risk factors and implementing strategies to mitigate them. Here are comprehensive approaches based on the latest research and expert recommendations to prevent the onset or recurrence of Achilles tendinopathy.

- Gradual Load Management

A key factor in preventing Achilles tendinopathy is the careful management of training loads. Sudden increases in activity level can place excessive stress on the tendon, leading to injury. Gradually increasing the intensity, volume, and frequency of training allows the tendon to adapt and strengthen over time. Monitoring training loads and ensuring a balanced approach can help minimize the risk of overuse injuries. We use Training Peaks for the monitoring of our runners and find it is a very sensitive and useful tool for this monitoring process. - Strengthening Exercises

Ongoing strength training and plyometric training, which involve loading the muscle-tendon unit under load, have been shown to be particularly effective in both the prevention and rehabilitation of Achilles tendinopathy, specifically around the calves and foot. These exercises can increase tendon strength and improve its ability to handle stress. - Flexibility and Mobility Work

Maintaining good flexibility and mobility in the calf muscles and the Achilles tendon can help reduce strain on the tendon. Regular stretching exercises, particularly for the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, can improve flexibility and decrease the risk of tendon overload. Just be aware that there is a U-shaped curve whereby too much flexibility can also cause injury. - Proper Footwear and Orthotic Support

Wearing appropriate footwear that provides adequate support and cushioning can significantly reduce the stress on the Achilles tendon in the short-term. For individuals with specific foot biomechanics that predispose them to tendinopathy, such as over-pronation or flat feet, custom orthotic devices may be beneficial. We advise that foot strengthening is focused on in the meantime if orthotics are reduced, in a progressive plan like in Foot Foundations, because long-term use of orthotics can result in feet that are weaker than prior to orthotics use, resulting in lower capacity to handle loads, and potentially more injuries in the future. - Cross-Training

Incorporating a variety of low-impact activities, such as swimming, cycling, or yoga, can help maintain fitness while minimizing stress on the Achilles tendon. Cross-training allows for continued physical activity without overloading the tendon, promoting cardiovascular health and muscular endurance without the risk of tendon damage. - Nutrition and Hydration

Adequate nutrition and hydration play a crucial role in tendon health. A balanced diet rich in proteins, vitamins, and minerals supports tissue repair and regeneration. Staying hydrated is also essential for maintaining the elasticity and flexibility of the tendon. For more detailed nutritional information, please reach out! - Rest and Recovery

Adequate rest and recovery periods are VITAL to prevent overuse injuries. Allowing sufficient time for the body to repair and strengthen after intense activity can help avoid the accumulation of stress on the Achilles tendon. Listening to the body and scaling back training when experiencing pain or discomfort is crucial. With that being said, many people experience tendinopathies after periods of no fast-movements or plyometrics, and so when they reintroduce the fast movements that load the tendon the most, they experience tendinopathy.

By incorporating these strategies into your training routine and daily life, you can significantly reduce the risk of developing Achilles tendinopathy. Remember, prevention is always better than cure, and taking proactive steps to protect your Achilles tendon can ensure long-term health and performance.

References

ACHILLES TENDON REPAIR CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Background. (n.d.). https://tco.osu.edu.

Arya, S., & Kulig, K. (2010). Tendinopathy alters mechanical and material properties of the Achilles tendon. Journal of Applied Physiology, 108(3), 670–675. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00259.2009

Baxter, J. R., Corrigan, P., Hullfish, T. J., O’Rourke, P., & Silbernagel, K. G. (2021). Exercise Progression to Incrementally Load the Achilles Tendon. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 53(1), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002459

Bohm, S., Mersmann, F., & Arampatzis, A. (2015). Human tendon adaptation in response to mechanical loading: a systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise intervention studies on healthy adults. In Sports Medicine – Open (Vol. 1, Issue 1). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-015-0009-9

Bramah, C., Preece, S. J., Gill, N., & Herrington, L. (2018). Is There a Pathological Gait Associated With Common Soft Tissue Running Injuries? American Journal of Sports Medicine, 46(12), 3023–3031. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546518793657

Cook, J. L., Khan, K. M., & Purdam, C. (2002). Achilles tendinopathy. Manual Therapy, 7(3), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1054/math.2002.0458

Crouzier, M., Dandois, F., Sarcher, A., Bogaerts, S., Scheys, L., & Vanwanseele, B. (2022). External rotation of the foot position during plantarflexion increases non-uniform motions of the Achilles tendon. Journal of Biomechanics, 141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2022.111232

Finni, T., & Vanwanseele, B. (2023). Towards modern understanding of the Achilles tendon properties in human movement research. In Journal of Biomechanics (Vol. 152, pp. 1–13). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2023.111583

Ganderton, C., Gaida, J. E., Cook, J., Docking, S., Rio, E., van Ark, M., & Gaida, J. (2015). Achilles tendinopathy: understanding the key concepts to improve clinical management. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/282001490

Järvinen, T. A. H., Kannus, P., Paavola, M., Järvinen, T. L. N., Józsa, L., & Järvinen, M. (2001). Achilles tendon injuries. In Current Opinion in Rheumatology (Vol. 13, Issue 2, pp. 150–155). https://doi.org/10.1097/00002281-200103000-00009

Langer, P. R. (2002). Achilles tendinopathy. In Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery – Series A (Vol. 84, Issue 11, pp. 2062–2076). https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-200211000-00024

Martin, R. L., Chimenti, R., Cuddeford, T., Houck, J., Matheson, J. W., McDonough, C. M., Paulseth, S., Wukich, D. K., & Carcia, C. R. (2018). Achilles pain, stiffness, and muscle power deficits: Midportion achilles tendinopathy revision 2018. In Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy (Vol. 48, Issue 5, pp. A1–A38). Movement Science Media. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2018.0302

Michaud, T. (2021). Injury-Free Running: Your Illustrated Guide to Biomechanics, Gait Analysis, and Injury Prevention. North Atlantic Books.

Rosenbaum, A. J., DiPreta, J. A., & Misener, D. (2014). Plantar Heel Pain. In Medical Clinics of North America (Vol. 98, Issue 2, pp. 339–352). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2013.10.009

Scott, A., Huisman, E., & Khan, K. (2011). Conservative treatment of chronic Achilles tendinopathy. In CMAJ (Vol. 183, Issue 10, pp. 1159–1165). Canadian Medical Association. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.101680

van der Plas, A., de Jonge, S., de Vos, R. J., van der Heide, H. J. L., Verhaar, J. A. N., Weir, A., & Tol, J. L. (2012). A 5-year follow-up study of Alfredson’s heel-drop exercise programme in chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 46(3), 214–218. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2011-090035

Yeh, C., Calder, J., Antflick, J., Bull, A. M. J., & Kedgley, A. E. (2021). Maximum dorsiflexion increases Achilles tendon force during exercise for midportion Achilles tendinopathy. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13974