What is work capacity?

Ever been confused by the term “work capacity”? Some say work capacity…. others say “VO2max”, “muscular endurance”, “cardiovascular exercise endurance”….. TOMATO-TOMA’TOE’!

In the world of strength and conditioning, the various terminologies for describing the same principles can often get confusing. For example, many people throw around the term “threshold” but don’t properly define anaerobic threshold versus aerobic threshold, or critical power versus functional threshold power (FTP – a cycling term). These multiple ways of saying the same thing get confusing, so if you’ve lost track of the definitions or meanings of work capacity versus endurance capacity versus regular endurance… you’re not alone.

After reading this blog, if you need help with your training, view our custom endurance packages HERE. Everything from today’s post, and more, can be listened to on a podcast Vital’s own Nicholas Simpson recorded on the Thermo Diet podcast (attached at the end of this post).

An easy definition to remember for work capacity

Perhaps you’ve heard “work capacity” talked about in an endurance context before. Classically, people use this in the context of referring to amazing endurance athletes with high “capacities” which typically people think of as their VO2max value, known as the maximum volume of oxygen that a person can consume and use for energy, typically tested during a maximal exercise test.

But what is exercise capacity, simply put, and why would we want to increase it?”

What most people think of is just very simple, the ability to do work. To do more work, either without stopping or resting, you’re able to accumulate more total volume, whatever it is that you’re working on. Simply, that’s work capacity.

As far as why you would want to do that, we think of it as just to get things progressing faster. You can only increase intensity so much, and so at some point you just need to do more work. Imagine being able to sprint 10m as fast as Usain Bolt, but then at some point, you likely need to extend that ability to 20m, 30m, and maybe even 100m if your goal is to be elite in the 100m race. To get your training progressing faster, then, you need your training to have components that increase your tolerance to handling more work.

In the rehabilitation world, we often refer to individual muscles as having their own capacities. So, for example, if you were doing our Foot Foundations program, we might refer to the calf’s endurance or exercise capacity, within some confines. For example, we might want to standardize our protocol and say, “How many calf raises can you do, at 1 raise every 2 seconds, up until you can’t maintain your original heel height or you lose cadence or bend your knee?” This would be a test for the exercise capacity of the calf muscles, if we felt that “endurance” or “the ability to do work in the calf” was important.

By contrast, in the endurance world, athletes typically go about building their capacity or endurance by pushing more and more scarcity onto their system. They try to make their body adapt harder to do more by eating less, and doing more work, and taking less rest during longer sessions doing more sessions. That would be the “more is better” dogma for training. Nonetheless, we can build endurance capacity this way.

Has it ever seemed backwards to you that when an endurance athlete trains for an event, they run/cycle/swim (or insert another mode) way slower and sometimes way longer than the event itself?

Take a 5k runner for example. The best in the world for men qualify for the 5k event at 13 minutes and 25 seconds. For women, they need to qualify with a time of 15 minutes and 20 seconds for the 5k event in order to be considered one of the best in the world. For men, that’s a 2 minute and 41 second kilometer, repeated 5 TIMES, or a 1 minute and 4 second lap of a 400m track, which most of us couldn’t even do! For women, the times are still uber impressive, working out to a 3 minute and 4 second kilometer repeated 5 TIMES, or a 1 minute and 14 second loop of a 400m track each lap.

If you’re unsure how fast that is, I would encourage you to go to a track and try to hit a single lap at those times, to see if you could even keep up with these runners for a single 400m of the 5k race. My hunch is that most of you reading this, absolutely could not. It is a full out sprint for the best in the world, and even for us average Joes, less than 1/10th of the same race pace feels like an all-out sprint. Oh, and that’s just to qualify for the Olympics, but doesn’t account for the fact that most of the athletes in the top 10 at those races can run up to a minute faster than those 5k times.

Even in the “middle distance” running events, the athletes are sprinting throughout the race, and speed is the major factor in who wins the race. Even over this 13-15 minute race, athletes are sprinting all-out to the finish line to come first. The athlete with the best speed and the best kick, will win.

Yet, when you look at most middle and long distance running training programs (and this is even worse as you extrapolate out to the general population in running races), there is a ton of long distance volume, and slow running in the program. In fact, most running programs of these distances involve volumes over 100-120k per week of running, in order to train for a 5k! Some would quote the 80/20 rule, which we discuss in other blogs on our old site (that we are in the process of transferring over to the new site), but is it really the 80/20 rule that explains these huge volumes of long slow running?

What if a runner wanted to improve their power and ability to run 5k faster, and they approached it from a *gasp* speed and power perspective? That’s a topic for another blog and another day, but for now, let’s continue to look at how we can approach work capacity, test it, and train it.

A technical definition for work capacity

In diving into the research, what do they say the technical definition of work capacity is, to help us round out our basic or layperson’s definitions above?

The technical definition of work capacity by Hass & Brownlie (2001) is that Work Capacity includes:

- Energetic efficiency

- Energetic efficiency is defined as the amount of physiological energy required to perform a given amount of external work. Energy expenditure is usually assessed by indirect calorimetry that converts oxygen uptake and carbon dioxide production to energy. External work is assessed simultaneously by the physical work performed on either a cycle ergometer or treadmill, usually reported in watts.

- Endurance

- Endurance is defined as the maximum length of time an individual can sustain a given workload. Physiologically, it depends on both oxygen delivery and oxygen use capacities of the working muscle

- VO2max

- The test of choice to assess aerobic capacity is the maximum oxygen consumption (VO2max) test. Protocols for the VO2max test have been standardized and widely used as an indicator of physical (aerobic) fitness. The test is designed to assess oxygen uptake at a point at which the subject has achieved a level of maximum exertion.

- Skill acquisition

From another paper, work capacity is defined as:

Work capacity is the ability to perform real physical work. Work capacity can be assessed by aerobic capacity, endurance, energetic efficiency, voluntary activity, and work productivity. Endurance is defined as the maximum length of time an individual can sustain a given workload (without rest) (Anbazhagan et al, 2016).

Aerobic work capacity versus anaerobic work capacity

It is well established that short and intense bouts of exercise rely on the alactic anaerobic energy systems and lactic anaerobic energy systems. However, the aerobic system is also relied on heavily during all-out high-intensity exercise. Aerobic energy can supply up to 40% of the energy required to do the work for a 30 second all-out test, and up to 50% of the work during a 1 minute all-out test. So, even for activities requiring lots of anaerobic contribution, there is a significant reliance on the aerobic system (Nunan et al, 2006).

For activities that are highly intermittent in nature (like hockey and many combat sports), it is thought that the aerobic contribution could be even higher.

The easiest way to test the aerobic work capacity is with a VO2max test! Though we only currently have the ability to estimate this through a field test called the Beep Test (20m Shuttle Run Test), booking a VO2max test would be a good way to get more data for yourself.

Testing Work Capacity

When we think of work capacity, we often think about testing to measure a starting point, a point for comparison with others, and for comparison as a follow up after a training block. To measure work capacity, we can do one of a few differently designed tests outlined HERE by Green (1995).

- Constant-Load Test

- This test requires the participant to maintain a constant power output or speed until it cannot be maintained. The load selected is higher than the subject’s VO2max and is typically selected to cause exhaustion in about 1 minute.

- A common test is the “anaerobic speed test” which requires subjects to run at 13 km/h and 20% grade.

- Serial Constant-Load Test

- These methods requires participants to be involved in multiple constant load tests. After the fact, the maximal work outputs are plotted over the durations and this can give information about the anaerobic work capacity.

- Typically, these tests last between 80 and 193 seconds but 2 minutes or more is suggested.

- Duration Test

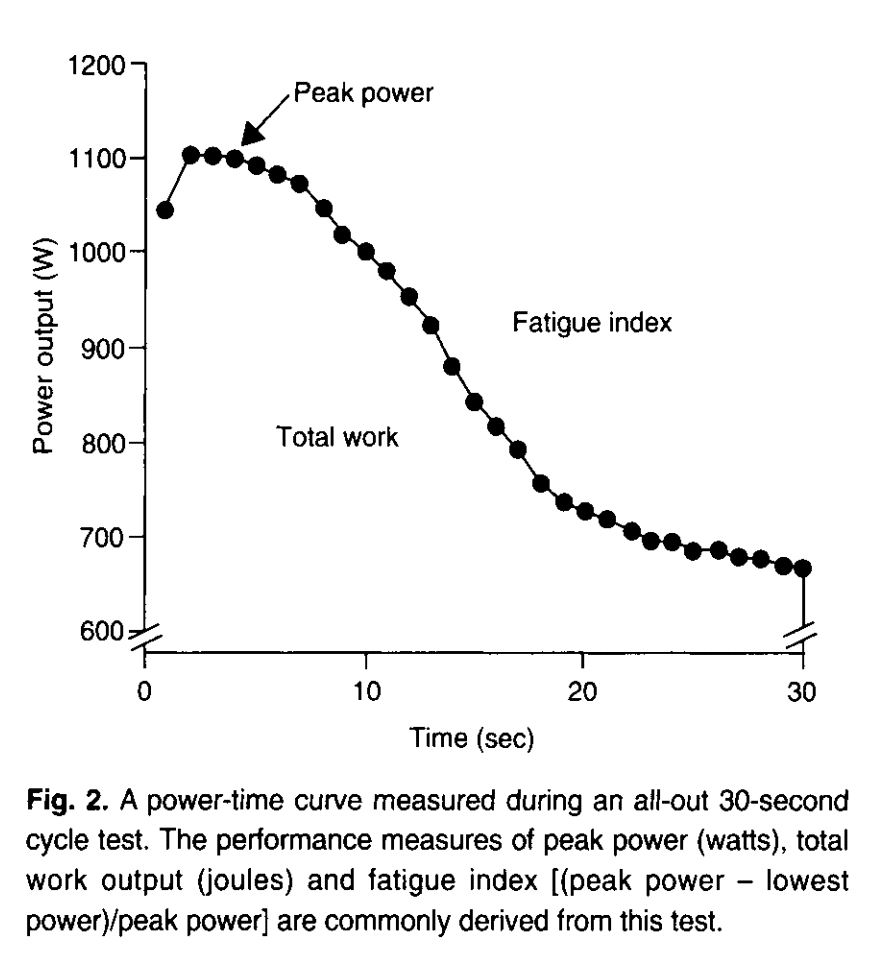

- Duration tests involve all-out work tests of 30 seconds, 45 seconds, 60 seconds, 90 seconds and 120 seconds most commonly. The most common of these tests is the 30 second all-out Wingate tests on a cycle ergometer.

- A sample test is shown below. The information from this test includes maximum power, fatigue index, and total work (area under the curve)

04. Force-Velocity Test

-

- Since true maximal power is a product of instantaneous values of force and velocity, and the two have a parabolic relationship, this can be another example for measuring capacity in a speed or maximal context

- Constant load maximal tests over a 30-45 second period on a cycle ergometer (while measuring maximal cadence), or various loaded sprint tests (while measuring speed) can be used.

In comparing two individuals, whoever did more work in that time period (either produced more power in Watts, or produced more force in Newtons, for example), wins. Similarly, even if 2 people have the same VO2max or 30-second all out Wingate peak power, but have different exercise efficiency or skills in performing the thing requiring effort, the one with better efficiency of movement might show better movement economy during a race, or less of a fatigue drop off during one of these all out-tests.

How do you improve your work capacity?

In this podcast about work capacity, Nick is interviewed about the best strategies for improving work capacity, and it is a great delve into a different way of thinking about endurance training. Spoiler alert: maybe the best way to improve endurance isn’t through endurance training….

Here’s a quick excerpt to get you excited before you have a listen to the podcast which we linked below!

“In that type of training, like where you deliberately push yourself into those lactic acid zones, tends to be some of the most stressful. So strategy 1 again is what strategies can we use to avoid that stress. Make sure you’re not wasting any energy… so that comes down to good technique you can use more or less when appropriate, and another one is probably a little bit more controversial in the pro-metabolic world by increasing your aerobic capacity, but if you have a good aerobic system, good ventilation, it’s like blood vessels, and when supplied to the muscles, the more energy you have coming into those muscles aerobically, the less you’re likely to get into that lactic acid zone, and the quicker you’ll be able to clear that when you do accumulate it.

The third strategy would be specifically like exposing yourself to a lot of training so that your body up-regulates the enzymes, like lactate dehydrogenase specifically to clear lactate. That’s probably my least favorite way to go about things. Because that sort of falls into kind of the middle training zone, and I would say, practically, the way I like to build capacity to maintain someone’s speed and power through that process is to use a polarized training model, which means you do a lot of really easy stuff for long periods of time, and you do some really really hard stuff for very short periods of time.

There might be a place for including a block of that in the scheme of things, but that wouldn’t be something I would go after often. Training wise my two favorite options would be like, 1) to do lots of really easy aerobic work. That’s how you build a good aerobic system that provides a lot of energy, it means you’re less likely to get there. It also means that you clear by-products faster when you do get there. And 2) being very energy efficient and technically sound, so that you’re less likely to get too many metabolic by-products. And then there’s a role for strength in that as well. Because the stronger you are, any other effort is going to be relatively easier, which means like you’re not, it’s 60% of your maps are spending less energy than if it’s 80% of your max, there’s definitely still a role of just being like, strong all around.”

Listen here or find it on your favorite platform to listen to Podcasts:

Link to the podcast not working? Head HERE for the original podcast.

Interested in having us coach you and break through your training plateaus? Head HERE for more info.

References

Anbazhagan, S., Ramesh, N., Surekha, A., Fathima, F. (2016). Estimation of work capacity and work ability among plantation workers in South India. 20(2): 79-83. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.197525

Green, S. (1995). Measurement of Anaerobic Work Capacities in Humans. In Sports Medicine (Vol. 19, Issue 1, pp. 32–42). https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199519010-00003

Haas, J. D., & Brownlie, T. (2001). Iron-Deficiency Anemia: Reexamining the Nature and Magnitude of the Public Health Problem Iron Deficiency and Reduced Work Capacity: A Critical Review of the Research to Determine a Causal Relationship 1,2. https://academic.oup.com/jn/article/131/2/676S/4686866