Introduction

Prepare to have some of the rules of endurance training that you’ve long known – shattered. Here I want to pull together some of the rebels of athleticism as they have dared to question conventional wisdom. In one corner, the revered 80/20 rule advocates training slow to get fast, while in the other corner, the coaches and athletes who champion building endurance on the foundation of speed.

In this blog we will challenge the status quo and embark on a quest to redefine the essence of endurance. Are you prepared to flip everything you’ve learned about endurance training on its head?

The 80/20 Rule: Unveiling the Foundation

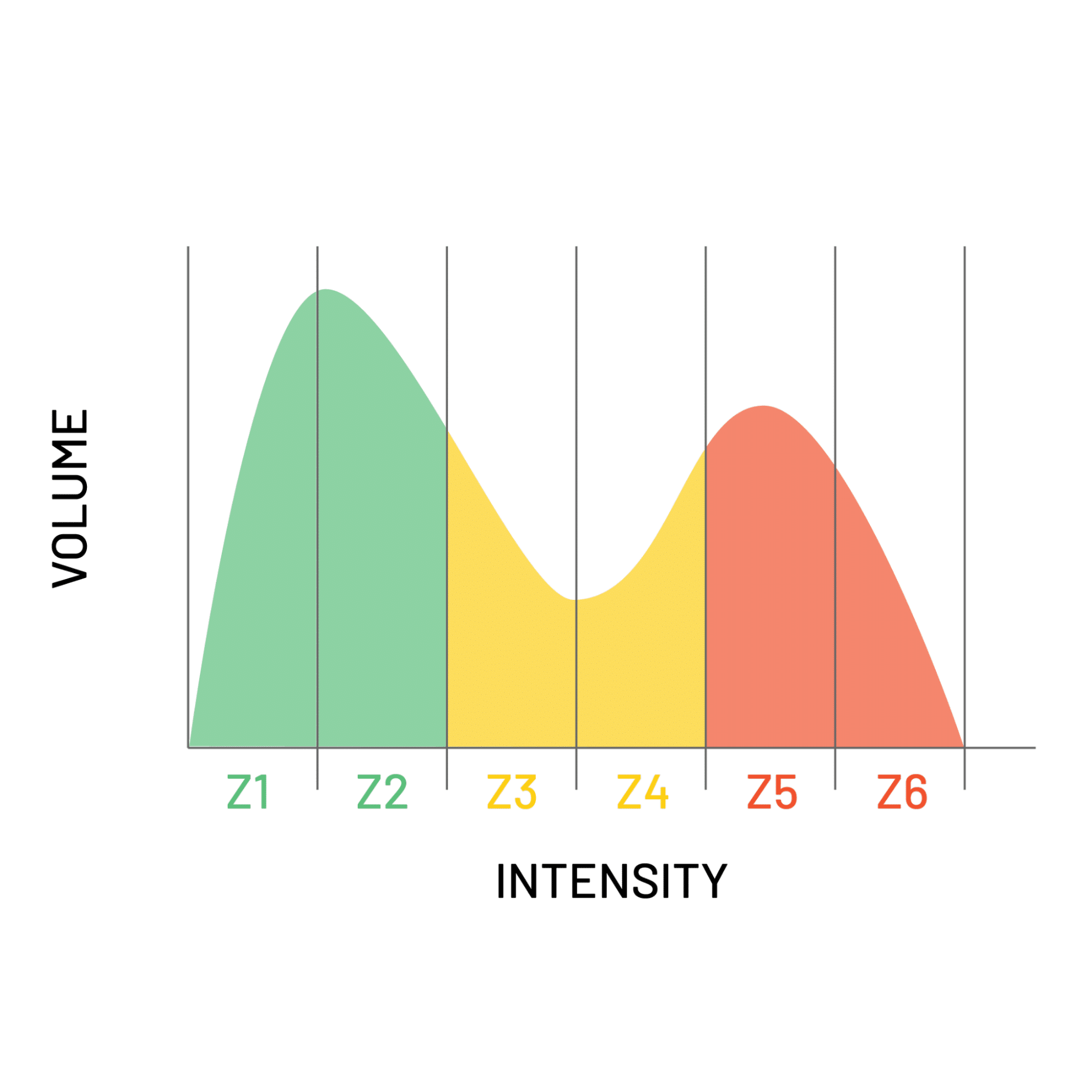

The 80/20 rule in endurance training, simply put, suggests that approximately 80% of an endurance athlete’s training time should be spent on slower, less intense cardiovascular training, while the remaining 20% can be dedicated to higher-intensity workouts. The idea behind this rule is to prioritize building a strong foundation of endurance by focusing on longer, low-intensity workouts that improve cardiovascular efficiency and overall stamina. By dedicating the majority of training to lower-intensity efforts, athletes can develop their aerobic capacity (also known as VO2max) and enhance their ability to sustain exercise for longer durations, ultimately improving their performance in endurance activities.

The unsuspecting source of the 80/20 rule in endurance training stems from observational studies that examined the training practices of elite endurance athletes. You read that right – rather than relying on controlled trials, the foundations of the 80/20 rule are purely observational. Researchers delved into the training logs and journals of successful athletes, meticulously analyzing their training distribution. Through these observational studies, a pattern emerged: the majority of these athletes seemed to dedicate approximately 80% of their training time to lower-intensity exercises and the remaining 20% to higher-intensity workouts. This finding sparked the development of the 80/20 “rule”, which gained traction as a training principle for optimizing endurance performance.

Burnley’s criticisms of Polarized Training are very interesting – and you can read the rest of his paper HERE if you’re interested.

One thing the authors of the Burnley paper emphasize is the importance of personalized training programs and argue for a more individualized approach that considers an athlete’s specific needs and goals. We couldn’t agree more. Taking that notion one step further, we think that asking hard questions and really evaluating the literature with a picky and critical eye, along with trial and error, and coaching experience in the field to back up theory, is where the magic happens.

Our hot take on speed first, then capacity

Hear us out.

You want to get faster in _____ distance.

You can perform the speed required, but not for the given time required.

This is common.

Think of a 10k runner (maybe you) who wants to improve their time by 5 minutes and get into the top 10% of runners in their age category. Think of a marathoner who wants to drop their time by 10 minutes and qualify for the Boston marathon. Think of the football player or skeleton athlete who needs to sprint faster, in order to impress agents or make the National team standard. The hockey player who wants to perform better overall (more speed but also better repeat sprint ability). Heck, this could even be by the clinical client who can’t stand up very fast or walk to the door in time to greet the mailman. Speed, in various contexts, dictates everything.

The traditional approach to improving speed is through a multitude of training around every energy system, at every pace, at various times throughout the year. In this traditional model, it is common for long aerobic blocks to be developed and worked on first, followed by speed much later in the off-season before competitions start.

Traditionally you’re told to:

– Do lots of training below “race” pace (for long distances, with little rest) – this is the 80%, typically. Even in speed-based sports like sprinting, they are told to do 400’s and even 800m sprints early in the off season, as an example.

– Do some training above that pace (for short distances, with lots of rest) – this is the 20%, typically. For sprinters, this might be accelerations or starts, in small quantities and volumes.

– When it comes time for race season, see if you’ve “got” the race pace required. In other words, find out what your race pace is on race day. However, it’s not common to include much training in the middle zones with the 80/20 rule; mostly when it comes to race day, individuals have no idea what the race pace feels like for extended periods of time.

This traditional approach in practice, for sport practice, literally looks like:

– Off season: do as much stuff that is as unspecific to your sport as possible (including movements, conditioning, and sports that don’t resemble your sport)

– Pre season: do intervals that still don’t really resemble your sport, but might be getting a little closer to your sport. Maybe some bilateral squats if you’re a unilateral sport, for example.

– In season: do intervals and strength training that is the most sport specific, but for most athletes still involves beating-around-the-bush in terms of conditioning workouts that are a little faster (and shorter) than their race pace, or ones that are a little slower (and longer) than their race pace.

What if that’s backwards?

The Charlie Francis Approach to Speed

Famous track coach Charlie Francis talks about a “short-to-long” periodization scheme whereby athletes train at race pace early in specific preparation phase of their off season. If they can’t hold a race pace yet, even for 10m, they train until they can. Once they can hold the race pace required for a short distance, the programming forces them to hold it for slightly longer and longer (15m, 20m) as they develop better capacity for that speed.

The opposite of this is long-to-short periodization whereby athletes would train with the longest distances the furthest from the race, and as the race approached at the end of their specific prep phases, they would drop the special endurance volume to more race-specific speeds and higher intensities, but propping the dropped volume up with speed and acceleration volume (which could become overwhelming for many athletes).

The long-to-short example for a 100m sprinter might be starting the specific prep phase with 400m and 800m runs, tapering that distance (and moving away from the slower speeds of the longer runs) down to 80m’s and 100m runs closer to comp. On the opposite end, in a short to long style periodization, the sprinter might start with 10 and 20m repeats, practicing “race pace” accelerations, and then end the specific prep phase with 100’s or 120’s. This latter model gives the athlete confidence that they can hit speeds and paces required for the 100, rather than the former model, where the athlete doesn’t practice race pace until right before, or even only during the competition.

As mentioned, in the short-to-long model, speed is integrated right from the beginning. For a 100m sprinter, Charlie Francis recommended 60m sprints right from the start of the program, tapering up to 120m sprints towards the competition block. The intensity on this type of program starts really high and stays pretty high as the volume drops nearing competition. There is still volume to be padded with some extra accelerations, starts, and easy-fast-easy or fast-easy-fast runs, but generally, the sprinter is used to the speed work throughout, and doesn’t get overwhelmed with speed work. Furthermore, you’re able to work on developing their speed from the start, and adding longer and longer bouts of holding the speed over time.

“I think there is a great deal of confusion for many coaches and athletes about what actual speed training looks like. To be fast you must run fast. To run fast you must set yourself up to succeed. You will not run fast if you are tired and tight as one example. You will not run fast if you are not able to give 95 percent effort. DON’T repeat runs for speed training if you are not feeling 95 percent effort is possible. The reason you don’t want to perform speed tired or tight is you will repeat runs performed poorly. Otherwise it’s likely you are practicing running that is not fast or technically sound. It’s essential you show up to practice each day and each workout feeling great, rested and ready to grab anything you are able to from each training session.”

– Coach Ange via Charlie Francis’ website

I love that quote because it really embodies the “Speed First, Then Capacity” motto, as well as the other analogy we use a lot in our social media posts, which are “Don’t Add An Engine To A Car With Flat Tires!”

Other versions of the speed first approach

Jack Daniels (the running coach – get your mind out of the gutter) includes speed work early in his off season training plans, too. That would be another example of a speed-first approach, but instead of using sprinters as Charlie Francis did, Jack Daniels mainly trained long-distance runners like marathoners. It’s interesting to see similar approaches in their training schemes for two very different categories of runners.

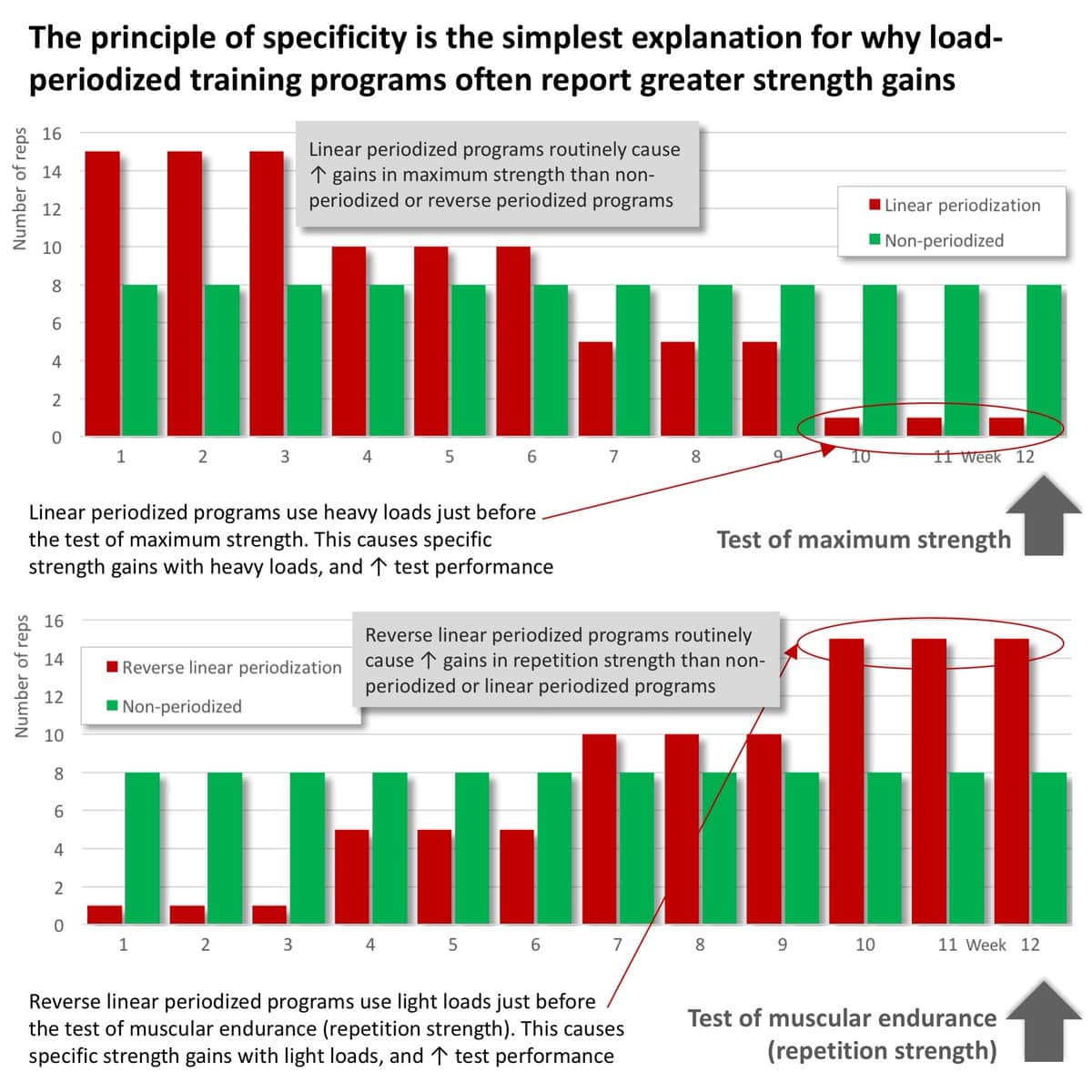

This approach is also in line with the concept of “Reverse Periodization”. Reverse periodization is a training strategy that flips the traditional sequence of periodization phases in endurance sports. Instead of starting with a base-building phase, athletes begin with a high-intensity phase focused on speed and power development, followed by a strength phase, and then transition to a lower-intensity, higher-volume phase closer to competition. The aim is to improve anaerobic capacity and power early on, gradually build strength, and finally enhance endurance capacity. While reverse periodization is not as commonly used as traditional periodization in the strength world, it is very popular in endurance training and in the track world, it provides an alternative approach that can be customized based on individual goals, event requirements, and athlete preferences.

As another infamous track coach once said, “Slow running makes you slow” – Les Gramantik. In my meeting with Les Gramantik recently in May 2023, I asked him how he likes to prepare his heptathletes for the 800m event – commonly known as the most deadly and difficult of all the heptathlon events. He said that he usually does nothing over 200m repeats in the preparation for their 800m, because “the faster you are at the 200, the easier the 800 will be.” Again, this is extremely counter to the traditional way of developing speed. I also interviewed Les earlier this year for a series I’m hoping to release one day. You can find the transcript for that first interview HERE.

Yet ANOTHER great track and football development coach says, “Speed is Life”. This coach is Glen Bruce and is a friend and mentor of mine, who helped me develop my ideas around speed during our many Zoom calls in 2020 during the pandemic. Glen and Les both are proponents of speed first training.

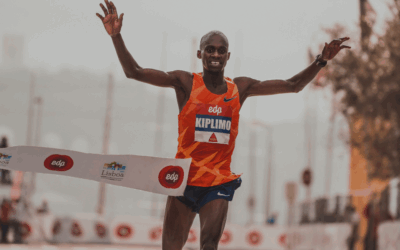

Although we’re talking a lot about sprinting in these last few sections, speed ALWAYS wins – even in the longest distance endurance events. How so, you say? Flashback to @courtneydauwalter winning the MOAB 240 mile race, winning by 10 hours 🤯.

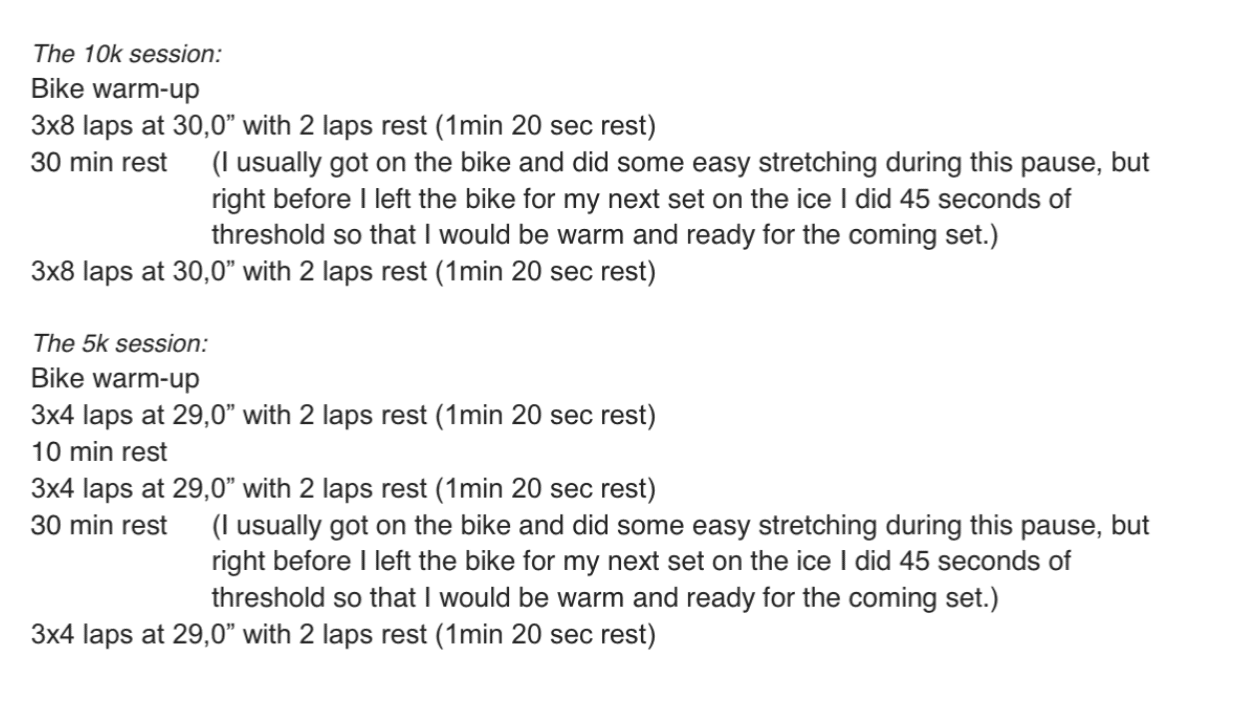

With two world records in the 10k speed skating event, @nils.vanderpoel published his training plan in which, no surprise, he ONLY skated at race pace during his in-season specific training (SPP) blocks leading up to competitions and the Olympics. He literally only ever did 30 second or 29 second laps in order to stay at the most specific interval length for his sport. Nothing faster, and nothing slower (except deep in the off-season). Here’s a snippet of his training plan that he published:

Imagine a program where you work specifically on the speed you need to complete the race at – rather than beating around the bush all the time?

Speed first. Speed always wins. THEN build capacity to hold that speed.

Unsure how this works in practice? We actually have a FREE ebook on building Work Capacity this way, that can be found HERE.

The Science Unveiled: Bridging the Gap

In the clash between traditional slow-first training and the alternative speed-first approach, it’s essential to examine the scientific evidence that underpins each perspective. Numerous studies have shed light on the physiological adaptations and performance outcomes associated with different training methodologies, helping us understand how they affect endurance athletes.

Aerobic Base Development and the 80/20 Rule:

The 80/20 rule, emphasizing low-intensity, long-duration exercises, finds its roots in the concept of developing a robust aerobic base. Research studies have demonstrated the importance of aerobic training in enhancing endurance performance. A study published in the Journal of Applied Physiology by Seiler and Kjerland (2006) observed that endurance athletes who followed an 80/20 training distribution, with 80% of training time spent at low intensity and 20% at high intensity, showed significant improvements in their aerobic capacity and race performances.

The rationale behind the 80/20 rule lies in the physiological adaptations that occur during low-intensity training. By engaging in sustained aerobic efforts, athletes can enhance their cardiovascular efficiency, increase mitochondrial density, improve oxygen utilization, and enhance fat metabolism. These adaptations lead to an improved capacity to sustain exercise for longer durations without excessive fatigue. Furthermore, research by Stöggl and Sperlich (2014) published in Frontiers in Physiology indicated that low-intensity training allows for better recovery and reduces the risk of overtraining or injury.

Speed as a Catalyst for Endurance:

Contrary to the traditional approach, some coaches advocate for building endurance on a foundation of speed and power. This perspective is particularly relevant for athletes competing in events that require a significant anaerobic component, such as short-distance running or cycling races.

Research has shown that incorporating high-intensity intervals and anaerobic training into an athlete’s program can elicit specific adaptations. A study published in Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise by Billat et al. (2001) found that interval training at intensities close to the anaerobic threshold can lead to significant improvements in aerobic capacity, lactate threshold, and race performance. By initially focusing on speed and power, athletes can develop their anaerobic energy systems, enhance their sprint abilities, and build muscular strength and power, all of which can contribute to better endurance performance during intense efforts.

Finding Balance and Individualization:

While the scientific literature provides valuable insights into the physiological effects of different training methodologies, it’s crucial to recognize that individualization is key. Each athlete possesses unique characteristics, goals, and event-specific demands, which should inform their training approach.

A review article by Mujika and Padilla (2001) published in Sports Medicine emphasizes the need for individualized training plans that consider an athlete’s fitness level, competition season, and personal preferences. Some athletes may respond better to a greater emphasis on aerobic base development, while others may benefit from integrating speed and power training earlier in their programs. Ultimately, it’s the careful balance between the two that may yield optimal results.

It’s worth noting that the field of sports science continually evolves, and new research emerges, refining our understanding of endurance training. Therefore, coaches and athletes should stay informed about the latest studies and seek guidance from qualified professionals to design personalized training programs that align with their specific needs.

Two Case Studies: Runner & Triathlete

One example of a speed-first approach I used recently, was with an injured runner who was referred to me by a physiotherapist who couldn’t seem to help the runner prevent knee swelling and mild pain when she ran. Modalities would help calm things down, but the swelling and soreness would always come back every time she tried to run again.

After an assessment, I noticed that the affected side had a big strength deficit that was causing her biomechanics to create a big inwards knee motion while she ran (also known as knee genu valgum). Inwards knee motion isn’t always something we need to worry about with athletes but paired with the symptoms, the strength deficit, and the uneven loading pattern, we created drills and a strength program to help pull her out of the valgus faster, to help her load the other end of the spectrum more when she ran. Once she got the hang of the technique we wanted her to use, we added speed first. So, I watched to ensure she was able to hold good technique as we added faster intervals over the course of weeks. Once she was able to hit 8mph for 30 seconds, I started extending the intervals to 40 seconds, 50 seconds, 60 seconds, and included some slower (6mph) longer tempo work too, always basing progression off of form. This is an approach that is typically opposite to the way endurance athletes add volume.

The second short case study I wanted to share was of an Ironman athlete who hired me to help her qualify for the Kona Ironman Championships. If you’re in the Ironman world, you know that this is the biggest of big races. I only had 3 months to identify gaps and develop her training plan in the lead up to her qualifying event, and with an experienced athlete like her who had been racing Ironmans for 10 years, it was an intimidating feat.

Upon analyzing her training journals, I noticed that she was all about the volume, and noted in her intake that she hated intense workouts, but that seemed like the exact gap we needed to fill. As Les Gramantik would say, if you want to get better for the 800m, train 200m speed. So, though we kept the volume moderate, I sprinkled in some intensity at the beginning of the 3 month block, extending those intervals to more sport-specific work towards the race.

In years prior to working with me, she would typically get a few minute improvements in the long 11-12 hour Ironmans, but in the Fall of 2022 after 3 months of working together, this athlete got a 40 MINUTE PERSONAL BEST, and instantly qualified herself for a spot at the Ironman World Championships!

I believe these approaches are similar in their speed-first approaches, despite one being a rehab case study and the other an ultra-endurance one.

Embracing the Endurance Revolution: Finding Balance

Though this article outlines a number of examples of a speed-first type of approach, this is by no means the only way to train individuals. While the 80/20 rule emphasizes low-intensity exercises to build a strong aerobic base, resulting in improved cardiovascular efficiency and endurance capacity, it is possible to focus on the other end of the spectrum for improvements, too. While scientific evidence supports both approaches, individualization is crucial. One of my favorite professors from my Master’s program, and acclaimed exercise physiologist, Doc Smith, always encouraged us to look deeper at the research into the outliers, rather than the averages, in the research. Each athlete possesses unique characteristics, and personalized training plans, as advocated by Mujika and Padilla (2001), consider factors such as fitness level, season, and preferences of the athlete to create the best approach. Striking a balance between the 80/20 rule and speed-focused training allows athletes to optimize their endurance training based on their specific needs, unlocking their full potential in performance.

If you want to learn more about how to develop work capacity by building speed on top of good technique, you can get our FREE eBOOK titled “Effortless Endurance: A guide to building Work Capacity in the weight room or on the track,” HERE!

References:

Beardsley, C. Specificity on the strength-endurance continuum is the simplest explanation for why linear load periodization causes greater ↑ in maximum strength, and why reverse linear load periodization causes greater ↑ in repetition strength (muscular endurance). https://twitter.com/SandCResearch/status/992328132505079808

Billat, V. L., Slawinski, J., Bocquet, V., Demarle, A., Lafitte, L., & Chassaing, P. (2001). Intermittent runs at the velocity associated with maximal oxygen uptake enables subjects to remain at maximal oxygen uptake for a longer time than intense but submaximal runs. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 33(11), 208-213.

Burnley, M., Bearden, S. E., & Jones, A. M. (n.d.). Polarized Training is Not Optimal for Endurance Athletes.

Coon, A. (2022). Sample speed workout for short to long speed skating. Retrieved from https://www.charliefrancis.com/blogs/news/sample-speed-workout-for-short-to-long-speed-training on February 23, 2022.

Mujika, I., & Padilla, S. (2001). Detraining: Loss of training-induced physiological and performance adaptations. Sports Medicine, 31(2), 79-87.

Seiler, S., & Kjerland, G. Ø. (2006). Quantifying training intensity distribution in elite endurance athletes: Is there evidence for an “optimal” distribution? Journal of Applied Physiology, 106(3), 1153-1161.

Stöggl, T. L., & Sperlich, B. (2014). The training intensity distribution among well-trained and elite endurance athletes. Frontiers in Physiology, 5, 295.

van der Poel, N. (2022). How to skate a 10k …and also half a 10k.

More About The Author

Carla Robbins, Owner of Vital Strength and Physiology Inc

Carla’s journey into the world of endurance training, strength and conditioning, and exercise physiology began with her Undergraduate Degree in Exercise Physiology at the University of Calgary and continued into her graduation with a Master’s in Exercise Physiology in 2016. Between working for the Canadian Sports Institute to the creation of her company Vital Strength and Physiology Inc, Carla is driven by a desire to find better ways to address complex cases in professional and everyday athletes and individuals.

Quick Navigation

- Introduction

- The 80/20 Rule: Unveiling the Foundation

- Our Hot Take on Speed First, Then Capacity

- The Charlie Francis Approach to Speed

- Other versions of the speed first approach

- The Science Unveiled: Bridging the Gap

- Aerobic Base Development and the 80/20 Rule

- Speed as a Catalyst for Endurance

- Finding Balance and Individualization

- Two Case Studies: Runner & Triathlete

- Embracing the Endurance Revolution: Finding Balance

- References