Introduction

If you’ve heard the cue “shoulders down and back”, congratulations, you have not been living under a rock for the past 50 years. I’ll admit, this used to be something I cued to many clients.

This cue is often given as a reminder for proper posture or body alignment, especially when you’re performing an activity like lifting, sitting, or playing sports. Although “shoulders down and back” is typically intended to improve posture and shoulder stability, it can actually interfere with natural shoulder mechanics and can actually be detrimental to health and pain.

Interestingly, I have worked with many clients with shoulder and neck pain, who come to me bragging about their awareness of their own bad posture. Often times, those that come in with some self-awareness of what they think is bad posture, have been told by their physical therapist (a general term I’ll use for the therapist family of massage, chiro, physio, osteo, etc), that it could be their posture that is setting up their discomfort or pain in their shoulders or neck. Some clients admit that though they try to keep the posture they are told to maintain – the “shoulders down and back” – that they find themselves drifting out of it frequently throughout the day. Some even go as far as to claim that as soon as they get out of the “down and back” posture – that they have neck flare-ups.

Read on to explore the reasons why “shoulders back and down” may not be the best advice for achieving optimal posture and movement. After reading this blog, if you still need help with your training or performance, reach out to us at Vital Strength Physiology HERE or learn about our Shoulder Foundations Program.

How do muscles pull us into postures?

First let’s talk about muscle – the muscles that attach to our bones and pull our bones and joints into various configurations. Without getting into the molecular details about how muscle works, we know that muscles have an original and an attachment point. All skeletal muscles have at least two attachments: the origin and the insertion. Skeletal muscles can only pull the origin and insertion closer together; they never push. This is in contrast to other muscles, like heart muscle tissue, that when contracts, can push blood out of its chambers. During contraction, a skeletal muscle insertion moves moves toward the origin. What makes one bone (the origin) stay in place while the other bone is the mover, is the contraction of other muscles that stabilize one of the two bones. This results in purposeful movement.

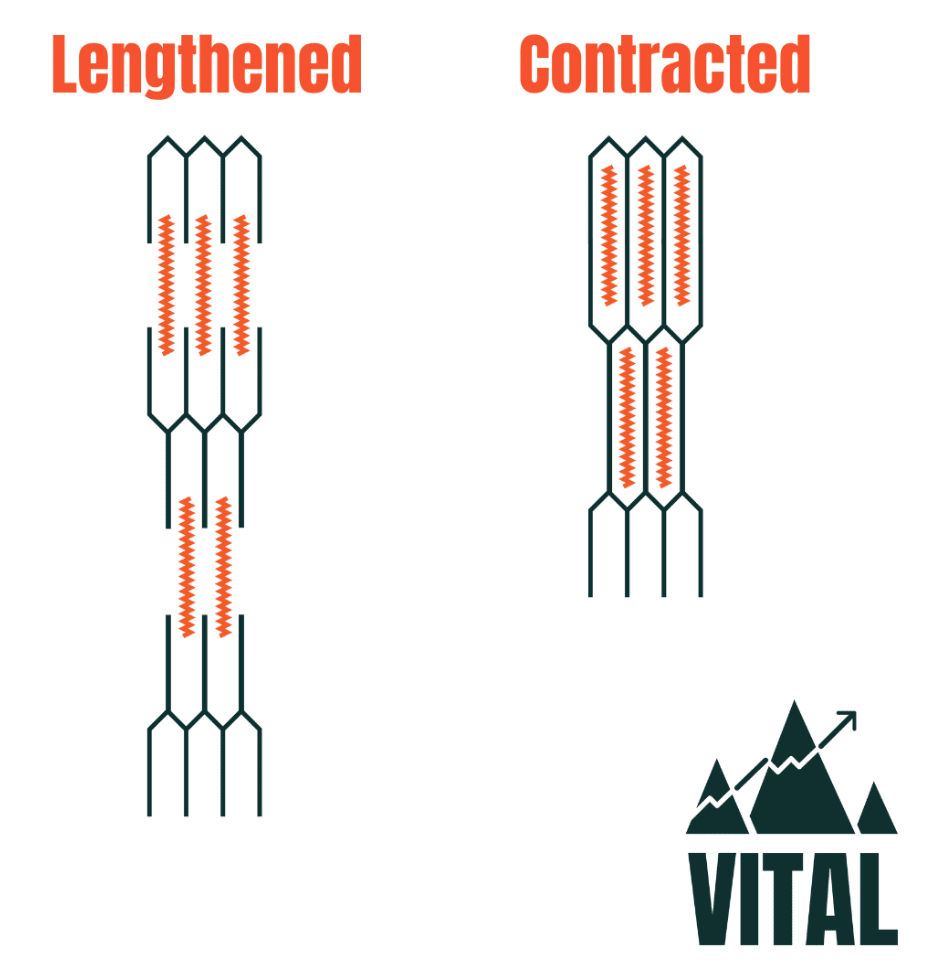

Muscle can exist in a range of lengths. A muscle can exist in a short or long length, and in various places within those extremes. It’s short when it’s contracting (duh) and long when it’s lengthening (duh). A muscle is short when contracting/shortening (imagine doing a bicep curl where you shorten the bicep muscle by pulling the weight to your shoulder).

A muscle can also exist in a very long state – during eccentric muscle contractions where the muscle contracts to resist the joint from going further or past it’s end range (imagine lowering the weight during a bicep curl towards the straight-elbow position). The muscle can exist in a neutral length, either in a relaxed state, or while contracting isometrically (resisting movement), OR at a moment in time through the concentric (bicep curl) and eccentric (bicep curl lowering) range. The lengthened state of muscle can also happen more passively, like when we do passive stretching of a muscle.

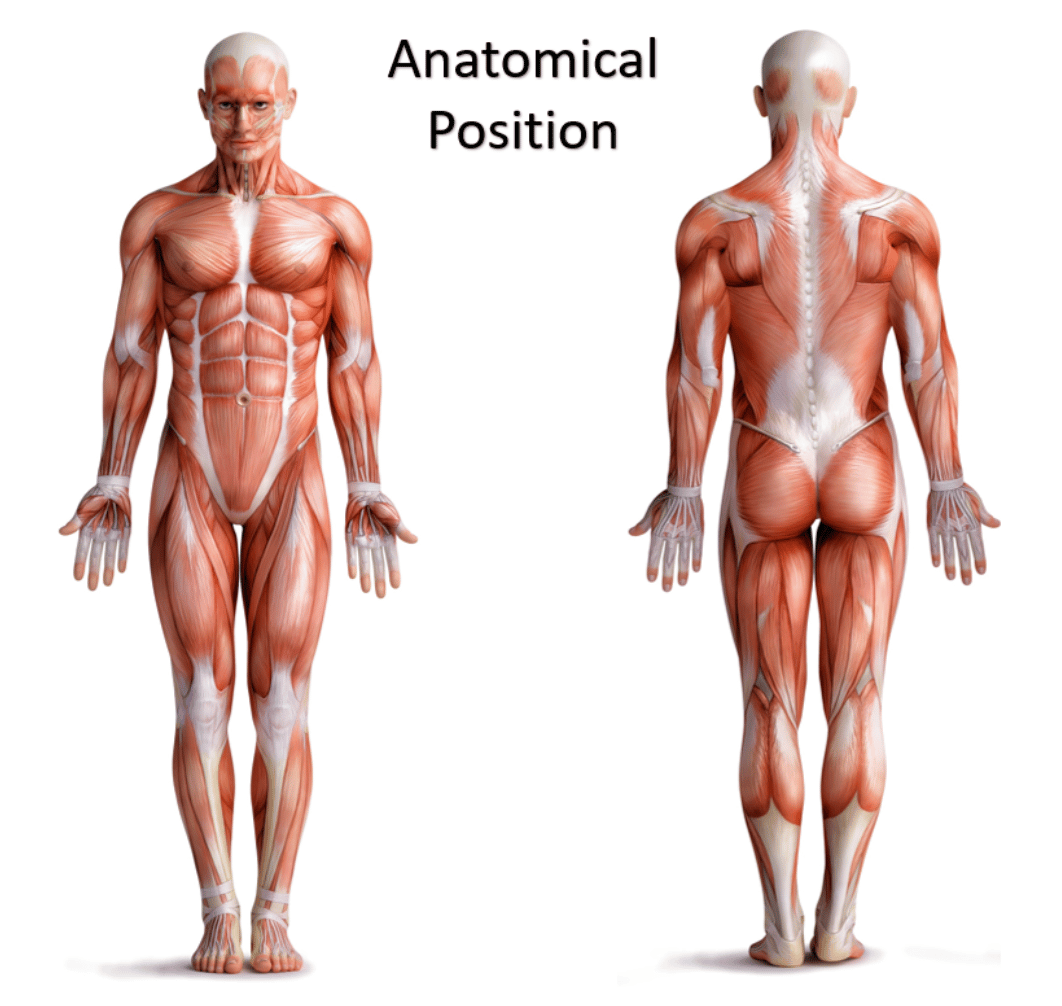

When we refer to neutral posture, or sometimes referred to as “good posture”, what we should be referring to is a state where most muscles are not torqued into a short OR a long state. Intuitively, this is likely pretty close to the anatomical position we’re taught in Anatomy classes.

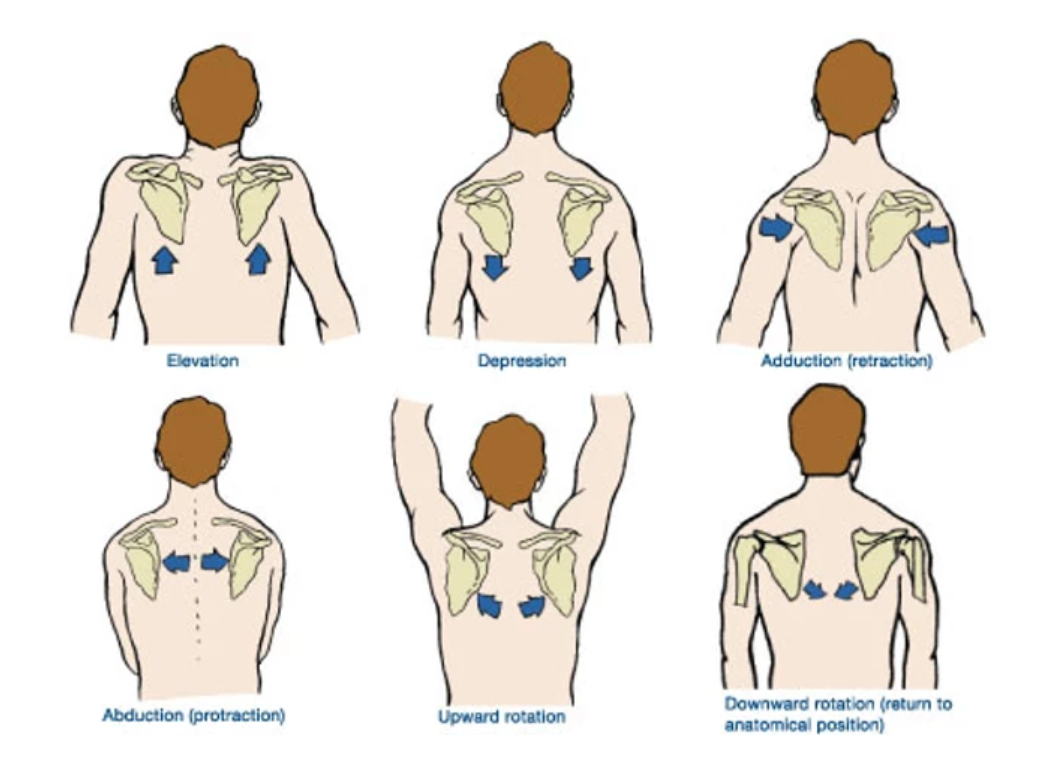

Now, back to the shoulder blades. In anatomical position, most of the muscles that move the scapula should be in a neutral length in the resting position. To name a few of the important movers of scapular motion, we have the rhomboids, the trapezius and the latissimus dorsi muscles (lats). There are many more that attach to the scapula (scaps) but let’s briefly explore those 3.

Different muscles have different actions on the neck and shoulder blades

Rhomboids

The rhomboid major is a skeletal muscle on the back that connects the scapula with the vertebrae of the spinal column. Its action is to keep the scapula pressed against thoracic wall and to retract the scapula toward the spine. The rhomboid major originates from the spinous processes of the thoracic vertebrae T2 to T5 and inserts on the medial border of the scapula. Its contraction helps pull the shoulder blades “back”.

Traps

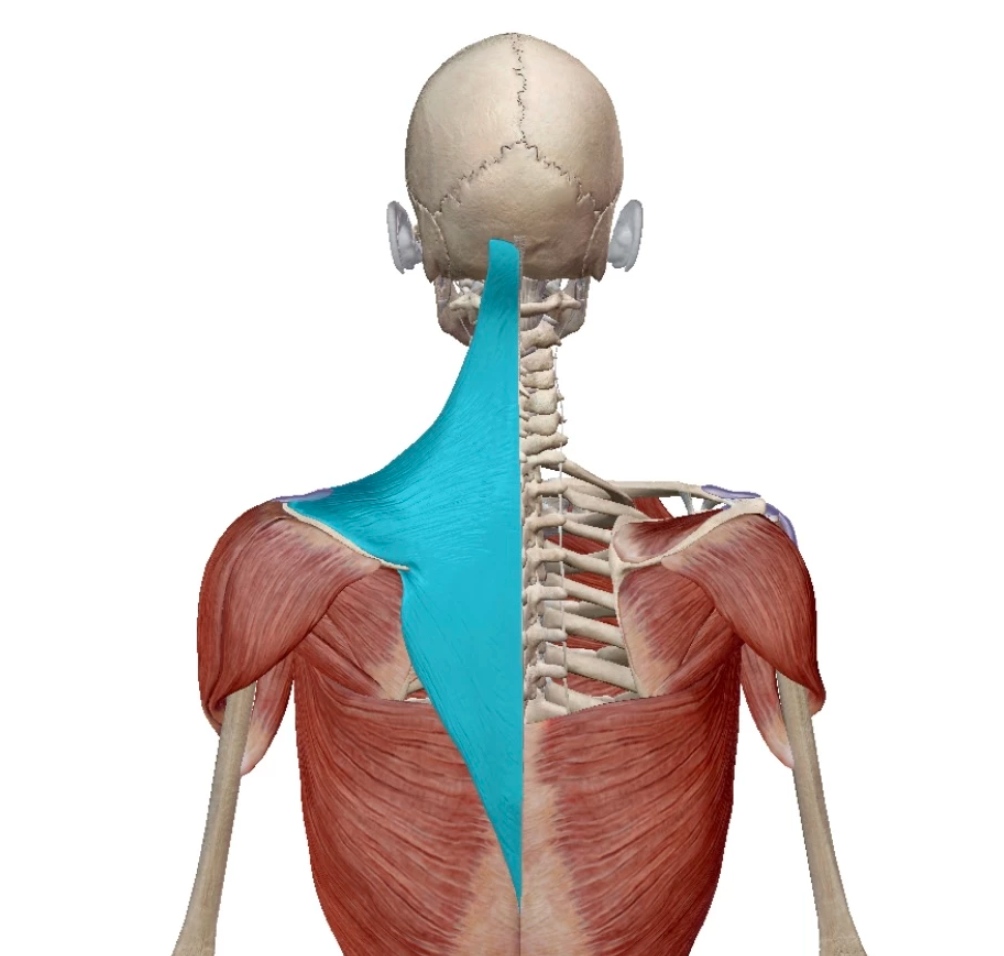

The trapezius muscle is shaped like a diamond and is typically divided into its superior/upper, middle, and lower fibres. Its upper fibres originate on the spinous process of the cervical and thoracic vertebrae of the spine. They insert into the scapula, acting to elevate and anteriorly tilt the scaps. The lower traps act as antagonists to the upper fibres, originating from the spinous process of the lower thoracic vertebrae and inserting near the end of the scapula. These fibres act to pull the scaps “downwards” and “back”.

Lats

The latissimus dorsi is the largest muscle on the back, and is responsible primarily for moving the shoulder joint and with secondary roles at the spine and scap. The origin of the latissimus dorsi is from the spinous processes of thoracic T7–T12, and it attaches to the humerus bone (upper arm). Due to bypassing the scapulothoracic joints and attaching directly to the spine, the actions the latissimi dorsi have on moving the arms can also influence the movement of the scapulae, such as the downward rotation of the scap during a pull up.

So to summarize, the rhomboids primarily act to pull the shoulder blades together or “back”, the middle and lower fibres of the trapezius muscle act to retract and depress the scaps to pull them “down and back”, and the action of the lats can help to indirectly downwardly rotate the scaps or pull them “down and back”. (The lats can rotate them even further than anatomical position as depicted in the figure below, if they are pulling into shorter lengths than just the resting length of the lats).

Why is “Shoulders Down and Back” a problem?

If you’ve been told incessantly to pull your shoulders down and back, you might be pulling these three (among other) muscles into their shortened positions, and forcing them to contract and use energy to stay in those positions. The body inherently likes to conserve energy, and has processes to avoid over-working. The central-governor-theory is literally a process built into us that causes the brain to stop allowing muscles to contract when they have been working hard for long periods of time. For the sake of postural argument, the low-level contractions used to adjust our posture are likely not strenuous enough to initiate the central governor to shut off these contractions, though.

If the same person that avoids certain shoulder positions continues to avoid movements of the scaps in their full ranges of motion, stiffness and tightness can be a created feedback loop whereby the muscles that are always short, and stay stiff and short, inhibiting the antagonist muscles to have their chance to contract, creating a feedback of weakness in those antagonists. The perfect example of this is examining people’s postures in movement assessments and getting an idea for which muscles tend to be shorter, more often, and which muscles tend to be lengthened, more often (perhaps because of their sport, as in the example below of swimmers versus pitchers, or in the case of people’s lifestyle).

Pulling shoulders down and back might not only create the “downwards and backward” muscles to stay short, it might be its starting position or the position they are already living in, further exacerbating the problem. This might cause the avoidance of using the antagonist muscles (in the case of chronic “down and back”, the upper traps and upward rotators of the scaps might need some more love), or it could make them weak over time. Further, the ongoing pulling of “down and back” can pull the antagonists, which in turn will pull hard on their attachment points. In the case of the upper trapezius muscle – constant pulling downward will cause a pull on the back of the head – the occipital bone – a common attachment point for the fascia and muscles of the skull – and a common starting point for people with muscle tension headaches.

Summary

In short – avoid staying in any particular posture. Except if you’re lifting heavy loads – in which case a neutral posture is likely best (Khoddam-Khorasani et al 2020). And incase you’re curious – I no longer cue clients to get their shoulders down and back with few exceptions.

Remember – the thoracic spine, where the scaps sit – is naturally rounded along the curved shape of the ribs, so having some forward shoulder posture might actually be “normal”. And – a post for another day – remember that effects downstream (ie pelvic positioning and perhaps even foot positioning) can have an influence of the activation of muscles in the upper body (Larsen, 2018) – likely for reasons related to the length of the muscle on its activation.

If you tend to suffer from upper shoulder/neck tightness and pain, try returning the muscles to a neutral length through strength training (which teaches the muscles to contract AND relax as well as to move through a FULL range of motion and settle in a more neutral length). As well, try shrugging slightly, a little more often throughout your day to get you out of a “down and back” posture that could be causing you grief. If if doesn’t work, you know where to find us for an assessment, or subscribe to the blog to be the first to get updates about future blog posts! Hit “login” above and you will be part of the community.

And if you’re struggling with shoulder issues, check out our Shoulder Foundations program!

More About The Author

Carla Robbins, Owner of Vital Strength and Physiology Inc

Carla’s journey into the world of endurance training, strength and conditioning, and exercise physiology began with her Undergraduate Degree in Exercise Physiology at the University of Calgary and continued into her graduation with a Master’s in Exercise Physiology in 2016. Between working for the Canadian Sports Institute to the creation of her company Vital Strength and Physiology Inc, Carla is driven by a desire to find better ways to address complex cases in professional and everyday athletes and individuals.

References

Anatomical Position Image – https://www.scientistcindy.com/anatomical-positions.html

Cressey, E. Pitchers vs Swimmers Image. https://ericcressey.com/pitchers-vs-swimmers

Khoddam-Khorasani, P., Arjmand, N., & Shirazi-Adl, A. (2020). Effect of changes in the lumbar posture in lifting on trunk muscle and spinal loads: A combined in vivo, musculoskeletal, and finite element model study. Journal of Biomechanics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2020.109728

Larsen, K. (2018). Postural cues for scapular retraction and depression promote costoclavicular space compression and thoracic outlet syndrome. ANAESTH, PAIN & INTENSIVE CARE, 22(2), 256–269. www.apicareonline.com

Motions of the Scap Image – https://www.acefitness.org/certifiednewsarticle/2384/correct-cues-for-scapular-motion/

Moustafa, I. M., Youssef, A., Ahbouch, A., Tamim, M., & Harrison, D. E. (2020). Is forward head posture relevant to autonomic nervous system function and cervical sensorimotor control? Cross sectional study. Gait and Posture, 77, 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2020.01.004

Murta, B. A. J., Santos, T. R. T., Araujo, P. A., Resende, R. A., & Ocarino, J. M. (2020). Influence of reducing anterior pelvic tilt on shoulder posture and the electromyographic activity of scapular upward rotators. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy, 24(2), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjpt.2019.02.002

Noakes, T. D., Peltonen, J. E., & Rusko, H. K. (2001). Evidence that a central governor regulates exercise performance during acute hypoxia and hyperoxia. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 204, 3225–3234.