Quick Navigation

- The Heel Striking Debate

- What is Heel Striking? (How Does it Compare to Midfoot and Forefoot Strike Patterns?

- Is Heel Striking Bad for Running?

- How Heel Striking Affects Your Knees, Hips, and Biomechanics

- What the Research Actually Says About Foot Strike and Injury Risk

- When Heel Striking Might Be a Problem

- Key Takeaways for Runners

- Ready to Future-Proof Your Feet?

- About the Author

- References

The Heel Striking Debate

If you’ve ever been told that heel striking is ruining your hips, knees or even speed, you’re not alone. The running world has been tangled in a debate about foot strike patterns for over a decade.

Heel striking, forefoot striking, or midfoot striking—which is best? Which will keep you injury-free? Which will make you faster?

It can be tempting to look for one “right way” to run, but the truth is far more nuanced. Runners deserve better than blanket advice like “never heel strike.”

We need science, not myths. Heel striking during running isn’t as bad as you’ve been told. In this post, we unpack what the evidence really says about heel striking during running and how it impacts your performance, injury risk, and biomechanics.

What is Heel Striking? (How Does It Compare to Midfoot and Forefoot Strike Patterns?)

Heel striking is a running pattern where the heel of your foot makes initial contact with the ground as you run.

Before we get into whether heel striking is bad, let’s define the different types of foot strike patterns:

- Heel Strike (Rearfoot Strike): Your heel is the first part of your foot to contact the ground.

- Midfoot Strike: Your foot lands roughly flat, with the heel and ball of the foot making contact simultaneously.

- Forefoot Strike: The ball of your foot lands first, with your heel touching down after.

These strike patterns describe how your foot hits the ground upon landing. You may notice your strike pattern changes depending on your speed. Many runners heel strike during easy or long runs but shift toward midfoot or forefoot during faster efforts.

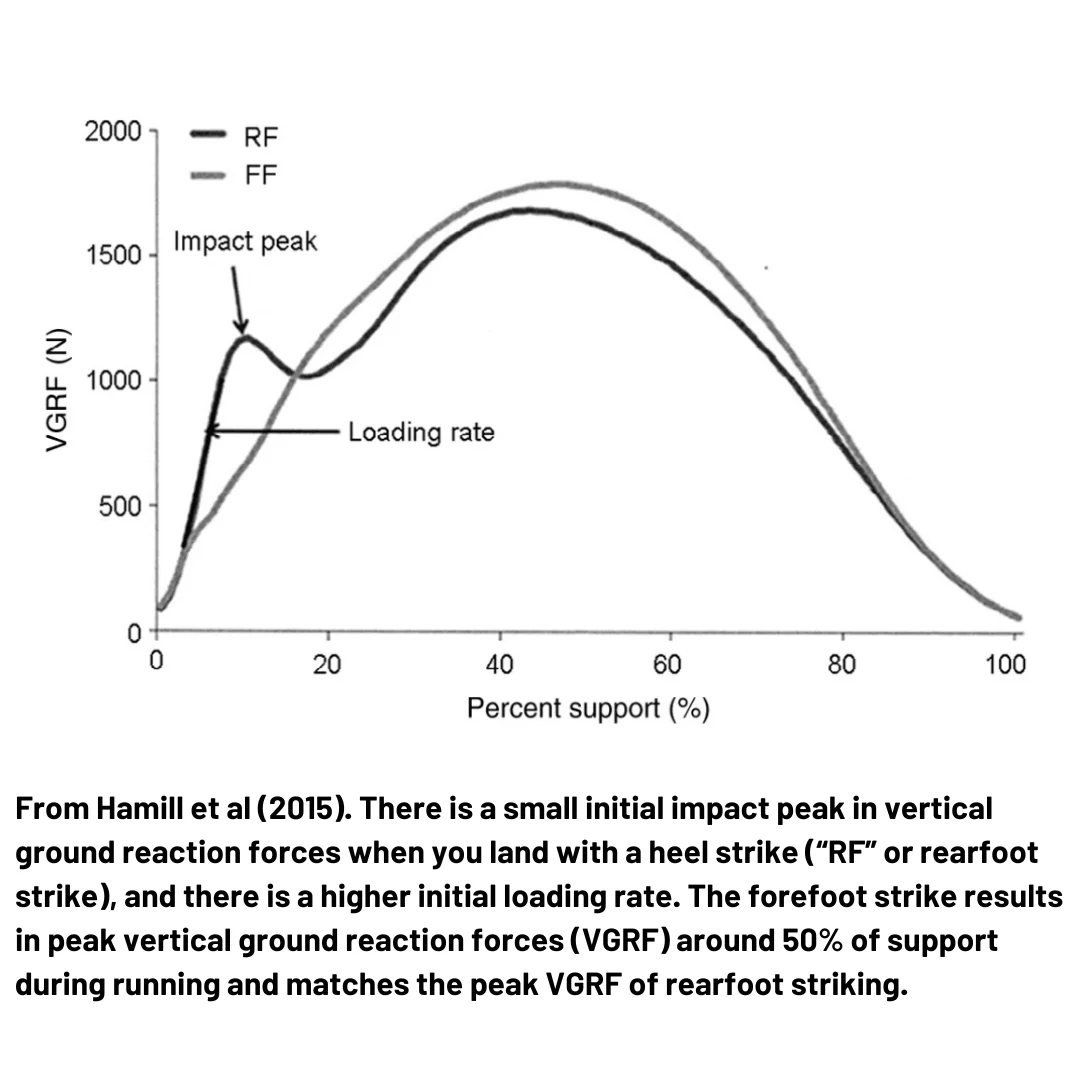

You’ve probably heard the claim: “A forefoot strike reduces impact forces compared to a heel strike.” It sounds simple, but it is also a misleading statement.

Here’s why saying that a forefoot strike is less impact is wrong:

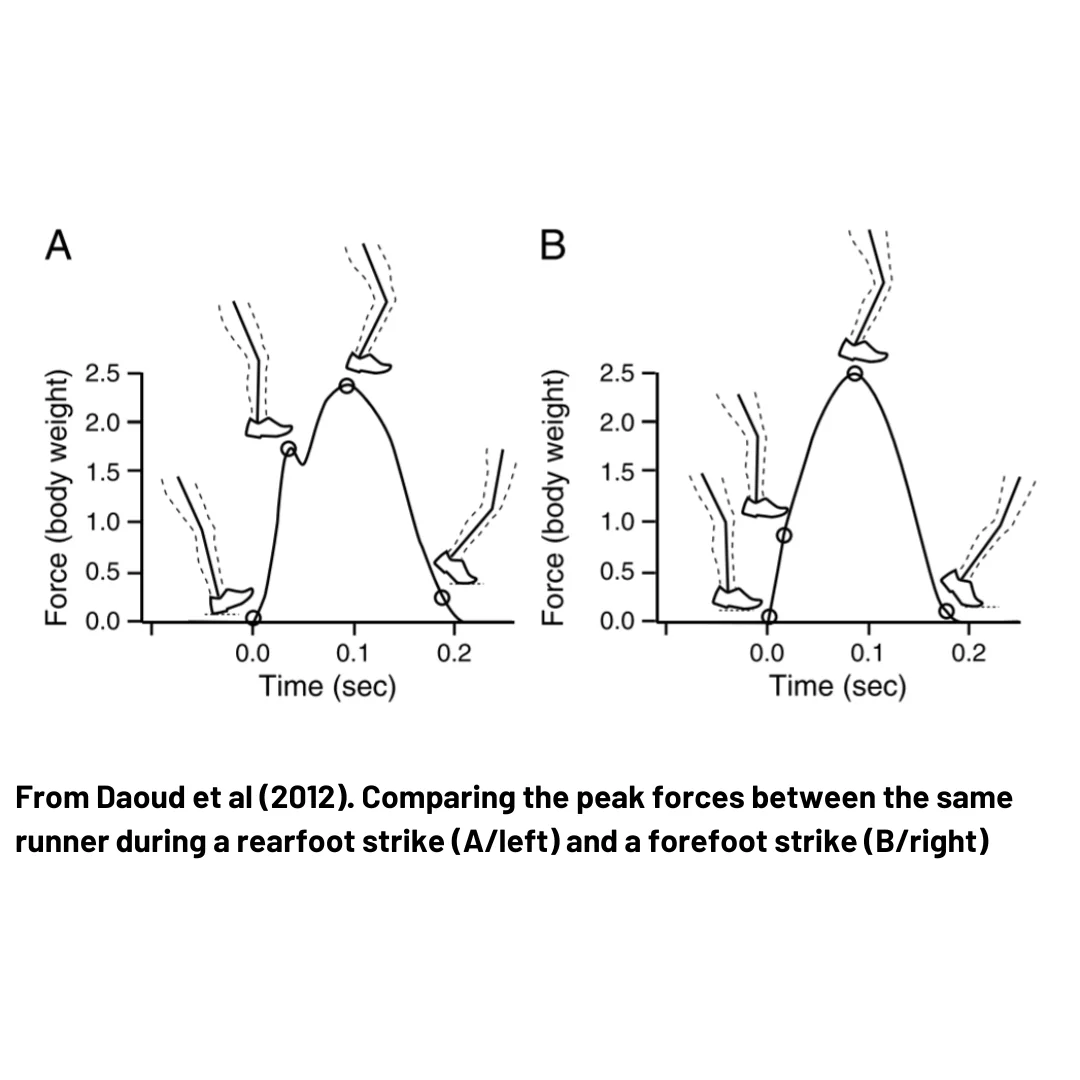

1️⃣ There’s an initial ground contact force that occurs when you hit the ground when you run—that first spike when your foot touches down. That is the “increased load rate” (Rice, 2016)

2️⃣ Your whole body continues moving over the foot until mid-stance where your body experienced peak vertical ground reaction forces (VGRF).

3️⃣ Peak ground reaction forces occur at mid-stance, no matter how you land, and they are insignificantly different no matter how you decide to strike the ground in running.

That last part is the kicker—forefoot striking doesn’t magically eliminate impact—it just changes the initial spike and then also how forces are distributed.

When you heel strike—forces will be experienced more through the knee.

When you forefoot strike—forces will be experienced more through the foot and ankle.

These are important considerations if you’re an injured runner and are trying to return to some volume. Perhaps adopting a slightly different foot strike in the meantime will help offload that area, if changed in a slow and progressive way.

More on that later in this blog post.

Is Heel Striking Bad for Running?

The short answer: no.

The idea that heel striking is inherently harmful is one of the most pervasive myths in running. The belief largely stems from the “Born to Run” barefoot running movement in the early 2010s, which suggested that modern shoes cause us to heel strike unnaturally, leading to more injuries.

But research over the past decade has painted a different picture:

- 70-90% of distance runners are heel strikers—even many elite athletes. (Klein, 2021)

- Heel striking is often more energy-efficient at slower paces compared to forefoot striking. (Daoud et al., 2012)

- Changing your foot strike pattern can increase injury risk, especially if done suddenly. (Rice et al., 2016)

There is no conclusive evidence that heel striking leads to more injuries than other strike patterns. In fact, forcing yourself to become a forefoot striker may simply shift the load to different parts of your body (more on that next).

How Heel Striking Affects Your Knees, Hips, and Biomechanics

When you run, your body absorbs the impact of each step through your feet, ankles, knees, and hips. The way you land can influence how that load is distributed—but it doesn’t change the total amount of force your body handles.

A common argument against heel striking is that it increases the “braking force,” slowing you down and jarring your joints. This is partially true if you overstride—meaning your foot lands far in front of your body. Overstriding can increase stress on the knees and hips, regardless of foot strike.

However, if your foot lands under your center of mass (even with a heel strike), the braking force is reduced.

Key Biomechanics Insights:

- Heel Striking shifts load slightly more toward the knee and hip.

- Forefoot Striking increases load on the ankle, Achilles tendon, and calf muscles.

- Peak Ground Reaction Forces Are the Same Across All Foot Strike Types. Research by Hamill et al. (2015) showed that peak forces when your body is over your foot are not lower with a forefoot strike. The force is just distributed differently.

So, heel striking is not inherently bad for your knees. It simply means that your knees are absorbing more of the impact compared to your calves and ankles. With strong quads, or with progressively building up the resistance to that pattern over time (as the elites do and have), you’re Gucci.

What the Research Actually Says About Foot Strike and Injury Risk

A study often cited against heel striking tracking 52 NCAA cross-country runners found that heel strikers experienced more injuries. But this study had limitations—small sample size, lack of control for other factors like training load and footwear. More comprehensive reviews have since challenged this narrative.

A key takeaway from the British Journal of Sports Medicine is this: runners who are not injured should not change their foot strike pattern to reduce injury risk.

Changing your foot strike is not a magic fix to reduce injury risk. Injuries in runners are influenced by:

- Training volume and progression

- Strength and tissue capacity

- Recovery and sleep

- Footwear

Your foot strike is just one small piece of a much larger puzzle.

When Heel Striking Might Be a Problem

While heel striking is not inherently bad, there are situations where it can contribute to discomfort or injury:

- Overstriding: If your foot lands too far in front of you, regardless of strike pattern, it can increase stress on your joints.

- Persistent Knee Pain: Some runners with chronic knee issues find relief by adjusting their stride (often shortening their stride or increasing cadence).

- Sudden Changes: Rapidly shifting from heel striking to forefoot striking without adapting can overload your calves and Achilles, leading to injuries.

Key Takeaways for Runners

- Heel striking is normal. Most runners do it, including elites. It is not inherently bad.

- Avoid overstriding. Focus on landing with your foot under your body.

- Cadence matters. Increasing your step rate (e.g., 170-180 steps per minute) can reduce overstriding.

- Comfort is king. The best foot strike is the one that feels natural and allows you to run without pain.

- Build strength. Strengthening your hips, calves, and feet is a more effective injury prevention strategy than obsessing over foot strike.

Ready to Future-Proof Your Feet?

Strong, resilient feet help to absorb impact and mitigate running injuries—regardless of how your foot lands. And it’s a piece often forgotten about. That’s why we created Foot Foundations, a program designed to:

- Build foot and ankle strength

- Improve running mechanics

- Reduce injury risk

Interested in learning more? Learn how to build strong, resilient feet with Foot Foundations.

More About The Author

Carla Robbins, Owner of Vital Strength and Physiology Inc

Carla’s journey into the world of endurance training, strength and conditioning, and exercise physiology began with her Undergraduate Degree in Exercise Physiology at the University of Calgary and continued into her graduation with a Master’s in Exercise Physiology in 2016. Between working for the Canadian Sports Institute to the creation of her company Vital Strength and Physiology Inc, Carla is driven by a desire to find better ways to address complex cases in professional and everyday athletes and individuals.

References

Ahn, A. N., Brayton, C., Bhatia, T., & Martin, P. (2014). Muscle activity and kinematics of forefoot and rearfoot strike runners. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 3(2), 102–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2014.03.010

Ardigo, L. P., Lafortuna, C., Minetti, A. E., Mognoni, P., & Saibene, F. (1995). Metabolic and mechanical aspects of foot landing type, forefoot and rearfoot strike, in human running. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 155(1), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1716.1995.tb09943.x

Bergmann, G., Kniggendorf, H., Graichen, F., & Rohlmann, A. (1995). Influence of shoes and heel strike on the loading of the hip joint. Journal of Biomechanics, 28(7), 817–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9290(94)00130-X

Cavanagh, P. R., & Lafortune, M. A. (1980). Ground reaction forces in distance running. Journal of Biomechanics, 13(5), 397–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9290(80)90033-0

Cunningham, C. B., Schilling, N., Anders, C., & Carrier, D. R. (2010). The influence of foot posture on the cost of transport in humans. Journal of Experimental Biology, 213(5), 790–797. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.038109

Daoud, A. I., Geissler, G. J., Wang, F., Saretsky, J., Daoud, Y. A., & Lieberman, D. E. (2012). Foot strike and injury rates in endurance runners: A retrospective study. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 44(7), 1325–1334. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182465115

Delgado, T., Kubera-Shelton, E., Robb, R., & Hickey, J. (2013). Effects of foot strike on low back posture, shock attenuation, and comfort in running. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 45(4), 490–496. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31827a09e7

Fukuchi, R. K., Stefanyshyn, D. J., Stirling, L., Duarte, M., & Ferber, R. (2014). Flexibility, muscle strength and running biomechanical adaptations in older runners. Clinical Biomechanics, 29(3), 304–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2013.12.007

Hamill, J., & Gruber, A. H. (2017). Is changing footstrike pattern beneficial to runners? Journal of Sport and Health Science, 6(2), 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2017.02.004

Haruhiko, G., & Suguru, T. (2022). Foot strike patterns and running-related injuries among high school runners: A retrospective study. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.21.12396-3

Hesegawa, H., Yamauchi, T., & Kraemer, W. (2007). Foot strike patterns of runners at the 15-km point during an elite-level half marathon. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 21(3), 888–893. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-22096.1

Klein, M. (2021, June 9). It’s okay to be a heel striker. Runner’s World. https://www.runnersworld.com/health-injuries/a36650122/heel-striking/

Kleindienst, F. I. (2003). Gradierung funktioneller Sportschuhparameter am Laufschuh. Aachen: Shaker Verlag.

Kleindienst, F., Campe, S., & Graf, E. (2007). Differences between fore- and rearfoot strike running patterns based on kinetics and kinematics. Proceedings of the XXV ISBS Symposium, Ouro Preto, Brazil.

Larson, P., Higgins, E., Kaminski, J., Decker, T., Preble, J., Lyons, D., & Normile, A. (2011). Foot strike patterns of recreational and sub-elite runners in a long-distance road race. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(15), 1665–1673. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2011.610347

Lewek, M. D., & Yu, B. (2012). Accuracy of self-reported foot strike patterns and loading rates associated with traditional and minimalist running shoes. Human Movement Science Research Symposium, University of North Carolina.

Lieberman, D. E., Venkadesan, M., Werbel, W. A., Daoud, A. I., D’Andrea, S., Davis, I. S., Mang’eni, R. O., & Pitsiladis, Y. (2010). Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners. Nature, 463(7280), 531–535. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08723

Mercer, J. A., & Horsch, S. (2015). Heel-toe running: A new look at the influence of foot strike pattern on impact force. Journal of Exercise Science & Fitness, 13(1), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesf.2014.12.001

Michaud, T. C. (2014). Is it harmful to heel strike when running? Competitor Magazine.

Miller, R., Russell, E., Gruber, A., & Hamill, J. (2009). Foot-strike pattern selection to minimize muscle energy expenditure during running: A computer simulation study. Proceedings of the American Society of Biomechanics Annual Meeting, State College, PA.

Napier, C., Fridman, L., Blazey, P., Tran, N., Michie, T. V., & Schneeberg, A. (2022). Differences in peak impact accelerations among foot strike patterns in recreational runners. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.802019

Nigg, B. M., & Enders, H. (2013). Barefoot running – Some critical considerations. Footwear Science, 5(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/19424280.2013.766649

Nigg, B. M., Hintzen, S., & Ferber, R. (2006). Effect of an unstable shoe construction on lower extremity gait characteristics. Clinical Biomechanics, 21(1), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.08.013

Ogueta-Alday, A., Rodríguez-Marroyo, J. A., & García-López, J. (2013). Rearfoot striking runners are more economical than midfoot strikers. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 46(3), 580–585. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182a42d1c

Rice, H. M., Jamison, S. T., & Davis, I. S. (2016). Footwear Matters: Influence of Footwear and Foot Strike on Load Rates during Running. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 48(12), 2462–2468. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001030

Walther, M. (2005). Vorfußlaufen schützt nicht vor Überlastungsproblemen. Orthopädieschuhtechnik, 6, 34.

Quick Navigation

- The Heel Striking Debate

- What is Heel Striking? (How Does it Compare to Midfoot and Forefoot Strike Patterns?

- Is Heel Striking Bad for Running?

- How Heel Striking Affects Your Knees, Hips, and Biomechanics

- What the Research Actually Says About Foot Strike and Injury Risk

- When Heel Striking Might Be a Problem

- Key Takeaways for Runners

- Ready to Future-Proof Your Feet?

- About the Author

- References