Introduction

Tendons are the unsung heroes of movement, bridging the gap between muscle and bone to transfer force and power. Yet, they’re often misunderstood or overlooked until something goes wrong—whether it’s an annoying ache or a serious injury. If you’ve ever wondered why your tendons hurt, what they need to thrive, or how to prevent injuries in the first place, this article has you covered.

Though I’m not a researcher of tendons, I’ve been struggling with my own tendinopathies this year (achilles, hamstring, and glute med/TFL tendon) so I’ve gone down the deep end with my research in 2024. Along with following and reading a ton of research by the tendon great, Keith Barr (lots of references from his in the reference section), I’ve also been following some newcomer tendon researchers in the space, like Jake Tuura. Along with endless reading, I’ve been experimenting on myself and our clients with tendon issues, so this article is a quick compilation of everything I’ve learned in 2024 that I’m bringing into 2025.

From my research and experience, this article outlines most important lessons about tendon health, rehabilitation, and performance I’ve learned so you can understand these VITAL structures better. From proper loading strategies to the role of nutrition, this guide will help you build resilient tendons for life.

After reading, if you still need help, you can contact us or get some free advice.

Top 16 Things You Should Know About Tendons

1. Load Management is Crucial

- Tendons thrive under appropriate, progressive loading.

- Overloading or underloading disrupts tendon homeostasis, leading to injury or degeneration.

- Inappropriate stress (too much or too little) leads to disorganization and weakening.

- Tendons “get mad” when you do too much, restarting inflammation and delaying the proliferation and remodeling phases (which take weeks to months).

- Tendons “get mad” when you do too little, decreasing collagen synthesis, which is necessary for rebuilding tendons.

- Loading a tendon daily helps reset its circadian rhythm: 12 hours of building, 12 hours of cleaning.

- Low-strain activities: 2+ minute isometric holds, blood flow restriction, medium-rep lifting. Low risk of pain or rupture.

- High-strain activities: Jumping, fast change of direction, short/long ground contact times. Higher risk of pain or rupture.

2. Metabolic Health Matters

- Poor metabolic health (uncontrolled blood sugar or blood pressure) leads to “bad blood,” which impairs healing.

- Excess glucose in the system can stiffen tendons by creating cross-links, making them brittle (not the “good” kind of stiffness) and prone to breaking.

- Emerging evidence links poor tendon health to systemic issues like diabetes, obesity, and inflammatory markers.

- Get that blood sugar under control so your tendons will thank you.

3. Nutrition can’t be missed

- Collagen-rich foods paired with vitamin C support tendon repair.

- Take 10–20g of collagen or 10–15g of gelatin 30–60 minutes before loading. Include 50–100 mg of vitamin C to aid collagen synthesis.

- Daily consumption is recommended, especially during early rehab phases when tendons are progressively reloaded.

4. Positions that flare them up

- Depending on what position you expose your tendon to, it could have a higher likelihood of flare up or overload

- Patellar tendon (below knee cap): might not like knees-over-toes positions acutely, and might prefer vertical-shin or hingy type movement patterns more.

- Achilles tendon (in the calf): might not like calf-stretching type positions acutely, especially if it is a tendinopathy of the attachment by the heel. Start with heels up isos, and even wear slight heel lifts to relieve the acute pulling

- Glute med tendon (side of the hip): might not like crossed-legs type positions so start with isos in slight hip abduction or external rotation.

- You can use your reasoning for the other tendons of the body or reach out if you’re confused

5. Tendon Adaptation is Slow

- Tendons adapt much more slowly than muscles, often requiring 12+ weeks for changes in stiffness or strength. Patience is key.

- We can load them daily but in small volumes to help “accelerate” the healing relative to resting or only training the tendon like a muscle (2-3 days/week)

6. Tendon Pain ≠ Structural Damage

- Healthy tendons have nerves only on the outer sheath.

- Unhealthy tendons develop nerve endings throughout, a sign of maladaptation.

- Tendon pain is often related to sensitivity and load capacity, not structural damage.

- Pain is normal and often reversible with proper training and loading.

7. Warm-Ups

- Warm-ups stiffen tendons, reducing strain for a given stress.

- Effective warm-ups: Harder activities like plyometrics or running.

- Ineffective warm-ups: Easy activities like stretching or calf raises.

- For injured tendons, avoid fast loading during acute flare-ups. Opt for isometric exercises instead with long holds (2+ minutes)

8. Eccentric and Isometric Training Are Beneficial

- Eccentric exercises (e.g., slow lowering movements) promote tendon remodelling.

- Isometrics reduce pain while maintaining tendon load capacity during flare-ups. They might also remove the stress shielding effect that happens with the healthy part of the tendon (that shields the unhealthy part from feeling load, a maladaptation)

- Long and heavy loading (e.g., 8+ second holds) helps squeeze water out of tendons, restoring balance.

9. Blood Flow and Tendon Healing

- Tendons are poorly vascularized, which slows healing.

- Mechanical loading enhances local circulation.

- Blood flow restriction is effective in early rehab phases, keeping pain and rupture risk low.

10. Anatomy of an Achilles Tendon

- The Achilles tendon spirals as it attaches to the heel.

- Training ankle rotation movements (e.g., pronation/supination, inversion/eversion) helps load fibres oriented in different directions.

- This spiral structure might apply to other tendons as well.

11. Tendon Rehabilitation Requires Specificity

- Rehab must target the affected tendon’s specific loading demands (e.g., running, cutting, lifting).

- General strengthening is a good starting point but isn’t enough for complete rehab.

- Eventually you want to progress to plyometrics. Check out our YouTube and search for “Tier” to view our public library of plyometric variations.

12. Age and Tendon Degeneration

- Aging leads to changes in tendon stiffness and composition, increasing injury risk.

- Strength and power training help mitigate these effects.

13. Antibiotic Use

- Fluoroquinolone antibiotics affect tendons negatively by disrupting collagen fibrils, increasing the risk of rupture and tendinitis.

- Check your history of antibiotic use if you’ve had a recent history of increased tendon tears

14. Programming for Tendon Loading

- Acute Phase (Painful Tendon):

- Start with isometric loading with long rests: 2–5 sets of 30-second holds, with 2-minute rests. Daily is okay if pain stays below 3/10 during and after.

- Phase 2 (Heavy & Slow):

- Add heavy and slow loading. Progress isometrics to harder or weight-bearing variations.

- Include heavy strength training for relevant muscle groups but avoid movements that “stretch” or “flare” the tendon.

- Phase 3 (Plyometrics):

- Introduce plyometrics while maintaining heavy strength training. Ensure no increase in pain after sessions or the following day.

- This is a short article outlining the basics, so I just wanted to point out that strength AND capacity (low rep and high rep) are eventually important for repairing the tendon. Doing low rep/high load in the morning and low rep/high capacity demand work at night tend to work well for loading tendons.

15. Why Tendons Tear

- Overload:

- Tendons can care if they get overloaded, for example in football if you get tackled at a vulnerable joint that overloads the joint and tendon, or with high forces like in sprinting

- Tendinopathy:

- Having a pre-existing tendon problem like a tendinopathy or tendon pathlology can set you up for more risk to tear a tendon

- You can get tested for tendinopathy with ultrasound

- Genetic condition:

- Certain genetic conditions make you more likely to tear a tendon. You can get tested for these conditions but its a catch-22 as you might not live life to the fullest if you are worried about the knowledge of your genetic condition

- Age and gender

- Males above the age of 25 and white ethnicity place you at higher risk for tearing tendons

16. Cortisone shots

- Never ever do a cortisone shot to your tendon. There is zero evidence to suggest that they work, and plenty of anecdotal evidence that they make everything worse for the tendon.

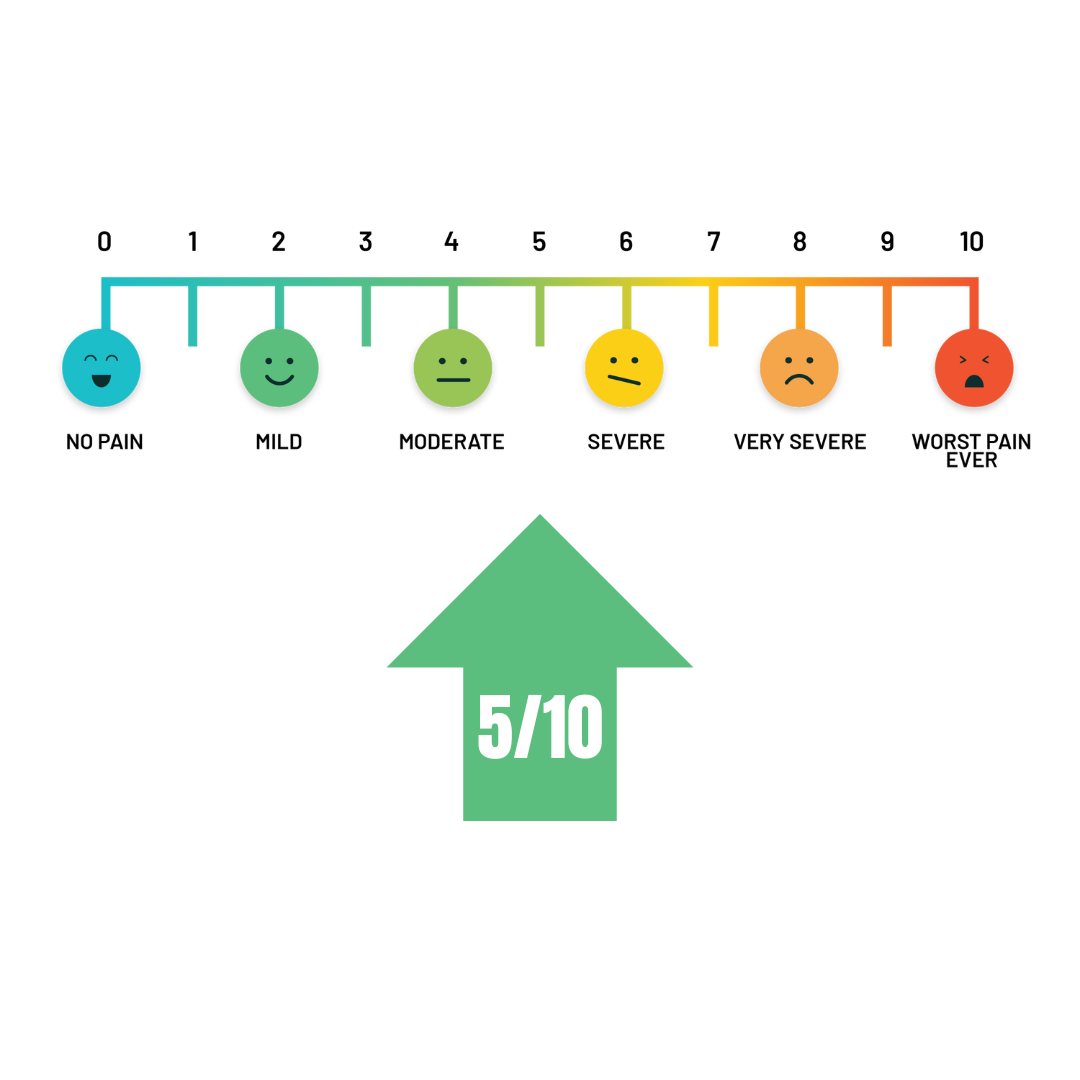

Pain Scale

Use this pain scale to modulate how much pain you should feel while loading the tendon (around a 3-5/10 or less) and keep the pain at the same level as the morning prior, or less. If you wake up with more tendon pain than the day prior, decrease the number of sets, reps, or the intensity of the exercises (load, force of the isometric push, etc)

Conclusion

Tendon rehab is NEVER linear so mini set backs are to be expected. Understanding and caring for your tendons is more than just avoiding pain—it’s about building a foundation for long-term movement and performance. Tendons thrive on the right balance of loading, nutrition, and care. Whether you’re recovering from an injury, looking to boost your athletic performance, or simply staying active as you age, these strategies can help your tendons stay strong, healthy, and pain-free.

Still unsure where to start? Reach out for personalized advice or explore our programs to find the guidance you need.

References

Baar, K. (2019). Stress relaxation and targeted nutrition to treat patellar tendinopathy. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 29(4), 453–457. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0231

Baar, K. (2006). Training for endurance and strength: Lessons from cell signaling. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 38(11), 1939–1944. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000233799.62153.19

Baar, K. (2017). Minimizing Injury and Maximizing Return to Play: Lessons from Engineered Ligaments. In Sports Medicine (Vol. 47, pp. 5–11). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0719-x

Baxter, J. R., Corrigan, P., Hullfish, T. J., O’Rourke, P., & Silbernagel, K. (2021). Exercise Progression to Incrementally Load the Achilles Tendon. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 53(1), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002459

Finni, T., & Vanwanseele, B. (2023). Towards modern understanding of the Achilles tendon properties in human movement research. In Journal of Biomechanics (Vol. 152, pp. 1–13). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2023.111583

Fletcher, J. R., Esau, S. P., & MacIntosh, B. R. (2010). Changes in tendon stiffness and running economy in highly trained distance runners. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 110(5), 1037–1046. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-010-1582-8

Järvinen, T. A. H., Kannus, P., Paavola, M., Järvinen, T. L. N., Józsa, L., & Järvinen, M. (2001). Achilles tendon injuries. In Current Opinion in Rheumatology (Vol. 13, Issue 2, pp. 150–155). https://doi.org/10.1097/00002281-200103000-00009

Kongsgaard, M., Qvortrup, K., Larsen, J., Aagaard, P., Doessing, S., Hansen, P., Kjaer, M., & Magnusson, S. P. (2010). Fibril Morphology and Tendon Mechanical Properties in Patellar Tendinopathy. American Journal of Sports Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546509350915

Lis, D. M., Jordan, M., Lipuma, T., Smith, T., Schaal, K., & Baar, K. (2022). Collagen and Vitamin C Supplementation Increases Lower Limb Rate of Force Development. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 32(2), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2020-0313

Narici, M. v., & Maganaris, C. N. (2007). Plasticity of the muscle-tendon complex with disuse and aging. In Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews (Vol. 35, Issue 3, pp. 126–134). https://doi.org/10.1097/jes.0b013e3180a030ec

Paxton, J. Z., & Baar, K. (2007). Tendon mechanics: The argument heats up. In Journal of Applied Physiology (Vol. 103, Issue 2, pp. 423–424). https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00426.2007

Rees, J. D., Stride, M., & Scott, A. (2014). Tendons – Time to revisit inflammation. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(21), 1553–1557. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2012-091957

Ross, R. K., Kinlaw, A. C., Herzog, M. M., Funk, M. J., & Gerber, J. S. (n.d.). Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics and Tendon Injury in Adolescents. www.firstdatabank.com

Shaw, G., Lee-Barthel, A., Ross, M. L. R., Wang, B., & Baar, K. (2017). Vitamin C-enriched gelatin supplementation before intermittent activity augments collagen synthesis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 105(1), 136–143. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.138594

Snedeker, J. G., & Foolen, J. (2017). Tendon injury and repair – A perspective on the basic mechanisms of tendon disease and future clinical therapy. In Acta Biomaterialia (Vol. 63, pp. 18–36). Acta Materialia Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2017.08.032

Starbuck, C., Bramah, C., Herrington, L., & Jones, R. (2021). The effect of speed on Achilles tendon forces and patellofemoral joint stresses in high performing endurance runners. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13972

Thomopoulos, S., Parks, W. C., Rifkin, D. B., & Derwin, K. A. (2015). Mechanisms of tendon injury and repair. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 33(6), 832–839. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.22806

Werd, M. B. (2007). Achilles tendon sports injuries: A review of classification and treatment. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. https://doi.org/10.7547/0970037

Yamamoto, N., Ohno, K., Mayashi, K., Kuriyama, H., Yasuda, K., & Kaneda, K. (1993). Effects of Stress Shielding on the Mechanical Properties of Rabbit Patellar Tendon. https://biomechanical.asmedigitalcollection.asme.org

Xergia, S. A., Tsarbou, C., Liveris, N. I., Hadjithoma, Μ., & Tzanetakou, I. P. (2023). Risk factors for Achilles tendon rupture: an updated systematic review. In Physician and Sportsmedicine (Vol. 51, Issue 6, pp. 506–516). Taylor and Francis Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913847.2022.2085505